Articles

The Folk Song That Made Us Americans

Saturday, June 30, 2012

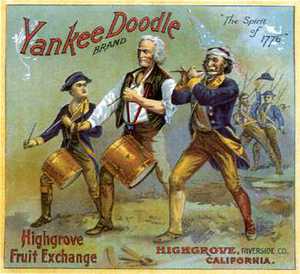

Yankee Doodle: the biography of America’s best-known song

It is impossible to be an American and not know the song "Yankee Doodle." It is played every Fourth of July, a plucky old tune that instantly conjures patriotic images of America's war of independence against Great Britain. But the wonderful story of how this ditty became the nation's first anthem, and the seminal role it played in helping Americans see themselves as citizens of that new nation, is less well known.

In "America's Song: The Story of Yankee Doodle," New York historian and author Stuart Murray has written what amounts to a biography of the tune, from its beginnings as a Dutch harvest song to its maturity as anthem of a new nation. The book is everything one wants a good biography to be, vivid, colorful, brimming with anecdotes and a rich sense of the times and places through which "Yankee Doodle" traveled, changed, and grew.

Despite enduring myths that Murray has a fine time skewering, the song's origins are clearly found in Dutch Colonial America. The Dutch word "jonker" referred to a country squire, "doedel" to a simpleton or fool. Early versions, drawn from a common harvest folk song, were used to lampoon the English farmers whose settlements neighbored, and soon encroached upon, the urban trading hives of Dutch America.

Verses teased the English as country bumpkins: "Jonker Doedel came to town / In his striped trousers / Couldn't see the town be cause / There were so many houses." Other Dutch nouns added clever plays on words, helping the song become a more acute satire as feelings hardened between the Dutch and English. The Dutch called their English neighbors "Jankes" (Johnnies), pronounced "Yahn-kees." But a slight alteration turned that into "janker," a Dutch epithet for a yelping dog, applied to a noissome, complaining neighbor, which the Dutch increasingly felt the English to be.

"Yankee Doodle" first went to war during conflicts between the British and French in the mid-1700s. By that time widely accepted as a satire of American provincialism, it was taken up by British regulars to mock Colonial militia. When local volunteers wore feathers in their hats, it reminded the British of London fops called "macaronies" because they affected the manners of Italian nobility. So the verse "Yankee Doodle went to town / Riding on a pony / Stuck a feather in his cap / And called it macaroni" ridiculed Colonials for having pretensions of being either gentlemen or real soldiers.

As tensions grew between Colonists and Great Britain, the tune was often played by the British army to taunt Americans. Its constant use had the unintended effect of making the redcoats appear even more like a foreign army of occupation, a separate entity hostile to local militia. It also unintendedly served to remind militia veterans what a fallible, inept force the British army had often been during the French wars.

The Revolutionary War began to the strains of "Yankee Doodle." British troops played it while marching to Concord in April 1775. On the bloody retreat to Boston, it was played back to them by triumphant American militia. Soon after, a British soldier grumbled that " `Yankee Doodle' is now their paean" and that New Englanders now "gloried in being called Yankees."

The song became a powerful force in helping Americans, who had always defined themselves by the colony in which they lived, to now think of themselves as patriots of a nation they were fighting to create. "Yankee" became the nickname for any supporter of the Revolutionary cause, and "Yankee Doodle" was played by American military bands during every campaign of the war. A new refrain was added to suit its new purpose as a cocky, morale-building march: "Yankee Doodle keep it up / Yankee doodle dandy / Mind the music and the step / And with the girls be handy."

Americans came to love the satirical tone of the song, how it described an army of citizens and not professional soldiers, who were overmatched but never outfought, underdogs who would prevail through their native wits, camaraderie, and righteousness of cause. The very fact that it had been used for so long as a British insult became an enormous source of pride and resolve.

In 1781, the Revolutionary War ended at Yorktown, Va., as Lord Cornwallis surrended to General George Washington. In one final insult, British troops were ordered to keep their eyes fixed on America's French allies. The French Marquis de Lafayette was enraged by this snub of the American army, but knew immediately how to remind the British just who had beaten them and to whom they were now surrending not only their army, but their colonies. He ordered the Continental Army band to strike up "Yankee Doodle," and British eyes snapped instinctively toward the Americans who played it.

Reprinted from Deep Community: Adventures In the Modern Folk Underground, originally appeared in the Boston Globe