Featured Stories

She Had A Song: Ronnie Gilbert, from the Weavers to Women's Music

Monday, June 8, 2015

She had a song: Ronnie Gilbert of the Weavers (1999)

Ronnie Gilbert, Judy Collins, Dar Williams

When America first heard the songs that would ignite the commercial folk revival of the 1960s, it was not the voices of Judy Collins or Joan Baez or Peter, Paul, and Mary that they heard. It was the voice of the Weavers.

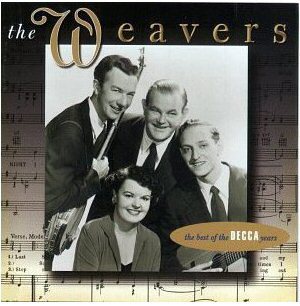

From 1950 until the anti-Communist blacklist destroyed their commercial viability in 1953, the Weavers -- Ronnie Gilbert, Pete Seeger, Fred Hellerman, and Lee Hays -- were the most popular singing group in America. So many songs now associated with the '60s revival, and permanently included in the American folk canon, were first popularized by them: ``If I Had a Hammer'' (which Seeger and Hays wrote), ``Kumbaya,'' ``Twelve Gates to the City,'' ``On Top of Old Smoky,'' ``Guantanamera,'' ``House of the Rising Sun,'' Woody Guthrie's ``This Land Is Your Land'' and ``So Long, It's Been Good to Know Yuh,'' and Huddie ``Lead Belly'' Ledbetter's ``Goodnight, Irene,'' ``Kisses Sweeter than Wine,'' and ``Midnight Special.''

``Ronnie is historically such an important part of our lives, because she was with the wonderful Weavers,'' said Judy Collins, who joins Gilbert, Holly Near, Dar Williams, and Linda Tillery's Cultural Heritage Choir in a benefit for the Women's Center of Rhode Island. ``I have known her on record for over 45 years; those were some of the first folk music recordings that were available back in the '50s. She was a great influence on me, just because she was a woman singing so strongly in a man's world.''

In 1950 and 1951, the Weavers sold more than 4 million records. Time called them ``the most widely imitated group in the business,'' and Carl Sandburg said, ``When I hear America singing, the Weavers are there.'' (Their career is displayed on a superb 1993 four-CD Vanguard set, ``Wasn't That a Time.'')

At 73, Gilbert is still a dynamic artistic presence, but rarely strays far from her Berkeley, Calif., home. She just finished a run of her musical based on Studs Terkel's book ``Coming of Age'' at the San Jose Repertory Theater, and remarked that this may well be her last concert appearance in New England.

In 1949, the four leftist singers had no idea of the legacy they were creating when they accepted a job at the Village Vanguard in Greenwich Village. They simply wanted to see if they could present traditional folk songs in a way that would appeal to urbane, pop-friendly audiences.

``We were four very politically motivated people, interested in doing what we could for the music we loved and for social action,'' Gilbert said. ``Part of social action at that time was to raise the consciousness of any audience to folk music, just to the idea that these songs existed.''

They avoided the overtly political songs they knew from their involvement in the labor and civil rights movements, but insisted on presenting folk as a multiracial, multicultural form. Their rise was astonishingly quick; their first single, the Hebrew ``Tzena, Tzena'' backed with ``Goodnight, Irene,'' was released on Decca after that first nightclub stint. It remained No. 1 on the Hit Parade for more than four months.

But the forces of McCarthyism were just as quick. Red Channels, the organ of the blacklist, first mentioned their leftist sympathies in 1950. Initially, it did not interfere with their string of hits, but by 1953, Decca had dropped them, radio stations refused to play their records, and a television series was canceled before it premiered.

Of course, to the rebellious generation coming of age in the 1960s, forcing music underground made it more alluring. Teenagers like Collins in Colorado and Near in California devoured their records. Gilbert became a signal beacon in a music landscape peopled with docile pop stars like Doris Day and Patti Page. It was not just what she sang, it was how she sang.

``For me as a female singer looking for role models,'' said Near, ``it was hearing her voice soar above these men's voices. There was something about her enthusiasm, as if there weren't any boundaries on her voice. She just stuck her chest out, threw her head back, and sang with abandon. There seemed to be a kind of body language that was all full of expansion, this kind of `here I am and here I come' stance.''

Williams said she believes that strength of purpose is what drew her to singers influenced by Gilbert, like Collins and Joan Baez. To her, it didn't matter so much what Gilbert was singing; the politics was in the stance she took, the way she sang.

``I think the presence of strong women in music -- not just politically, but strong in singing songs about life and its meaning -- are the reasons I am a folk singer, too,'' she said. ``And my sense is that the women who inspired me, like Joan Baez and Judy Collins, got that from Ronnie. It's all well and good to say women can be strong; it's quite another to have a precedent.''

Collins said that Gilbert gave her the hope that she could make music on her own terms. ``I've been able to make music in the way I've wanted, to carve out a life in which I write, I sing, write books, and tour,'' she said. ``It's a wonderful gift to be able to do that, and to have had people who showed me that was possible. I think the Weavers' influence has to do with giving people the right to be who they are musically, and to offer kind of a through-line to the tradition of that.''

Gilbert was pleased to see so much of the Weavers' repertoire and vocal style shape the early '60s folk revial. It was, after all, what they had set out to do: to place these American folk songs into the cultural mainstream. But it was not until she heard Near's feminist music in the '70s that she was certain their legacy would continue.

``I sat down and my heart just melted over it,'' she said. ``The way she sang, the songs she sang, the form the songs were in, the lyrics, all seemed to be doing in her day and with her issues what the Weavers did with the issues in our time.''

Tillery is letting a vocal nodule heal and declined to be interviewed. But in an e-mail response, she revealed a quieter dimension to the web of inspiration Gilbert has spread. She wrote how much it meant when Gilbert, aware of Tillery's efforts to bring African-American folk songs to modern audiences, gave her a rare 19th-century book of songs from the slavery era.

Gilbert stressed that her legacy did not begin with her. She inherited it from labor radicals like Mother Jones (whom she has portrayed in a musical) and from outspoken African-American singers Marian Anderson and Paul Robeson. She sees that legacy blazing now in the politically fired songs of Williams and Ani DiFranco, and knows the sparks she and the Weavers struck so long ago will continue to glow and to be stoked by new generations.

``The strength that people draw from the Weavers, and that Holly talks about in me, is the same strength I found in Marian Anderson and Paul Robeson,'' she said. ``It's about a kind of crazy, singing insistence on being in this world; that we have a right to be here and be heard -- and an obligation to be heard. Something of that is in my voice, was in Marian Anderson's voice, is in Holly's voice and Ani's voice and is a tremendously important thing for people to hear. That's our value, and I don't know if we ever do it knowingly; we just do it because that's what came down to us. That's our heritage.''