Articles

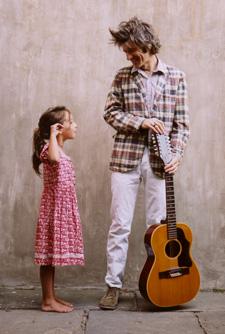

Dan Zanes & the family music movement

Monday, November 30, -1

Dan Zanes is all the rage in children's music these days. To hear the national media tell it - and his charming, folksy recordings have been touted in People Magazine, Rolling Stone, the New York Times Magazine and Entertainment Weekly - he is single-handedly making kiddy music hip for parents.

Just how he is doing this may surprise longtime folk fans. His recipe for hipness is stripped-down, acoustic covers of American folk standards like "Polly Wolly Doodle," "Rock Island Line," "Skip to My Lou," Wabash Cannonball," "We Shall Not Be Moved" and the always chichi "Washington at Valley Forge."

While his records are delightful in their musical friskiness and utter lack of condescension or perky pretension, they nestle warmly into a long line of folk albums released since the evolution of the family music movement in the late 1970s. The approach is strikingly similar to that taken by such family music pioneers as John McCutcheon, Cathy Fink & Marcy Marxer, Tom Chapin, Tom Paxton, and Sally Rogers.

Zanes knows this; he insists that he is not reinventing the children's music wheel, as so many pop pundits claim, but proudly standing on the shoulders of a long tradition of folk music for children and families. He constantly mentions Ruth Crawford Seeger's groundbreaking book, "American Folk Songs for Children" as a seminal influence, not only for repertoire, but for her deep understanding of how children interact with music. Lead Belly's huge influence on Zanes is proclaimed in the third sentence of his publicity bio, and he constantly cites American folk music as the bedrock of his musical voice and vision.

Yet to hear the mainstream press tell it, what he is doing is something utterly new, edgy and unprecedented in its urbane hipness. While Zanes is understandably grateful for the media buzz that has propelled him from Manhattan restaurant performer to national children's star, he is both disappointed and mystified that the mainstream press does not see his work the way he does, following in the footsteps of a long line of folk music for children; and more precisely, the family music movement that created music not for children alone, but for whole families to enjoy together.

Zanes, a former rock star with the Del Fuegos, says, "I know if I had been reading some of the things people wrote about my music - somebody making rock'n'roll for kids - I would just be running in the other direction, because kids get plenty of that. And I don't know if what I'm making has anything to do with rock'n'roll. For me, I feel like where my music is going is towards family music more than children's music. I keep getting this idea that there's this music out that there that is really for everybody; this space where the music can exist and be fun for everybody, without losing the kids along the way. I really believe in that shared experience."

His latest album, "House Party," on his own Festival Five Records, is a merry essay on the joys of social music, deliberately designed to feel like it's roaming from room to room in a big, musical house party. The sound is spare, frisky and acoustic.

One reason his music has such a hip cache is that he invites pop and rock stars to join him on his records. On his first family album, "Rocket Ship Beach," he sang "Polly Wolly Doodle" with Sheryl Crow, and "Erie Canal" was given a deliciously droll reading by Suzanne Vega. On "House Party," he is joined by Bob Weir, Debbie Harry, and African star Angelique Kidjo, singing an achingly gentle "Jamaica Farewell."

He has never put together collections of songs exclusively meant for children. This was among the first things he learned from Ruth Seeger's book, and from the approach to family music pioneered by her stepson Pete, Woody Guthrie, Ella Jenkins, and Lead Belly. They shared adult songs with kids, treated with fun-loving introductions, and opportunities to participate. The roots to the recent family music movement lie in the classic children's recordings these artists made for Folkways in the 1940s and '50s.

According to Cathy Fink, among the most influential artists and thinkers in that movement, Pete Seeger's passion to include everyone in his music cast a rich shadow over the current crop of family artists.

"Why? Because one of Pete's greatest talents is involving everybody, getting everybody to sing and making them feel that this is our music," she says. "This is not me doing something for you; this is something we can do together."

To trace the recent roots of this folk-fueled subgenre of family music, though, you need to see what a hardscrabble, grassroots world folk music was in the 1970s, after the last spurts of the great commercial revival of the '60s had fizzled. What circuit there was for the few folk artists who toured then, including Fink and John McCutcheon, was small and intensely localized. There was no national media source for exposing folk artists to audiences, only a few small, local public radio shows.

According to Fink and McCutcheon, much of the thinking that inspired the family music movement was purely practical. Audiences were small and cultivated in highly personal ways in those days. Fan bases were literally built fan by fan, because gigs were so few and far between. Success in one venue meant absolutely nothing in the next town. Artists wanted to maximize every opportunity to expose their music to new fans, but at the same time, never wanted to give a performance everyone might not enjoy.

"By my own example," says Fink, "back in the '70s, when I would perform for folk clubs, I said to them, 'Well, if I'm doing a Friday show, maybe we should look at putting me in a school program during the day, doing something for the kids. Maybe then the kids would get interested in coming to the evening concert, and tell their parents.' And many of these venues started hosting Saturday family concerts."

Immediately, though, these folk performers realized they were playing to adults as well as kids in their children's shows. Every chance to expose folk music to audiences, particularly new audiences, was precious; and nobody wanted to put adults through a grueling experience listening to numb-headed kiddy ditties. Following the Seeger standard, artists consciously designed their programs to please everyone who was there.

Around that time, Canadian children's performer Raffi began getting exactly the same media buzz Zanes is getting today. His collections of songs, while aimed at kids, were produced with beautiful, state-of-the-art studio production. Kids loved his non-patronizing way of singing about their lives, and parents were deeply grateful that his music was so enjoyable for them to listen to - in stark contrast to the increasingly gimmicky, sound-effects-laden drivel produced by mainstream pop.

If you can point to a single moment when the modern family music movement was born, it would be 1983, with the release of John McCutcheon's groundbreaking children's album "Howjadoo." Like Raffi's recordings, it was superbly produced, the most expensive album the Appalachian folk singer-songwriter had ever made. But it s influence lay even more in how he conceived the album.

"To boil down all my thinking about 'Howjadoo,'" McCutcheon says, "the basic criteria was that I wanted this to be the album that would settle the argument in the car about what everybody was going to listen to. I wanted it to be something the kids could really enjoy, and not just be enduring for mom and dad - and vice versa. This was going to be something the whole family would enjoy."

When he did interviews following the album's release, he began referring to it as a family music album, not a children's music album. Then he would stress the differences, echoing similar changes happening throughout the folk world in its approach to performing for children. Popular performers like Fink, Sally Rogers, Tom Paxton, Tom Chapin and Bill Harley were also stressing that their shows were meant for whole families, not just for kids to clap along to and parents to patiently endure.

Fink sees a long, slow, almost organic curve in the development of this thinking. "To tell you the truth," she says, "I think we always recognized that we were getting a family audience, knowing that kids don't just get dropped off at these shows and picked up an hour later. But because of who we were as folk performers, we have this desire to connect with and interact with everybody in our audiences. We want to reach them all."

Around this time, daytime children's concerts throughout the folk world began being billed as family concerts, and the difference stressed to media, performers and presenters. For the first time, people in the folk world began to realize there was something important happening here, a genuine movement towards a new way of perceiving and presenting culture for kids and parents.

"The way the folk music community tends to work, in my opinion," says McCutcheon, "is that things really do percolate up from the grassroots. What I saw happening is that those of us who were very specific about saying 'Trust us, you'll have more people come if you call it a family concert' were drawing larger audiences, so the next time someone come through, the promoter would say, 'Let's call it a family concert.'"

These folk artists were already moving on to what, in retrospect, was the inevitable next step: creating music that explored issues whole families face together. Again, this happened simultaneously throughout the folk circuit in the '80s, but nowhere was its influence felt more than in conversations between McCutcheon and his best friend, renowned political songwriter Si Kahn.

They began looking for song ideas, talking about children's music in a radical new way. As McCutcheon put it, they didn't want to be "generational imperialists," but to break down the barricades between children's and parent's repertoires.

"When a kid loses his first tooth, for example," McCutcheon says, "It's a big deal for the whole family. It was fun as writers to present ourselves with the challenge of writing songs that had multiple portals for different people, but the common ground of experiences families share together."

As a true folk troubadour, McCutcheon was also listening to his fans. At their request, he wrote "Happy Adoption Day," which deepened his thinking about providing a musical soundtrack for modern families, what he calls "a liturgy for daily life."

One day, seeking song ideas, McCutcheon and Kahn leafed through a calendar looking for occasions that involved whole families: holidays, the first day of school, the first snowfall, the last day of school, baseball's opening day, fishing season, and walking-through-the-woods time.

The result was the friendly '90s epic most often called McCutcheon's Seasons Cycle, four Rounder albums exploring the passing of the year in the lives of American families. Mostly co-written with Kahn, the songs explore everyday themes like "New Kid in School," "Halloween," "World Series," "Labor Day," "The Flu," "Hot Chocolate," "Going to the Prom," "Junk Mail," "Frog on a Log," "Mud," "Ice Cream Man," and "Riding My Bike." In all of them, the goal was to offer these experiences from every aspect of the family experience.

"The aim was not for crossover appeal," McCutcheon says, "but for a completely shared repertoire."

Another milestone in the evolution of family music was a series of theme recordings made by Cathy Fink and her partner Marcy Marxer, beginning in 1993 with Rounder's "Help Yourself."

"The first three family albums Marcy and I did were still being called kids music, although the production values were clearly meant to be appreciated by parents," Fink says. "Then we began to look at where the holes were. What songs would actually be useful at this point?"

"Help Yourself" focused on issues of safety and self-esteem. The songs were still aimed at kids, but in ways that made them useful, fun tools for parents and teachers to discuss important issues with children. In "Nobody Else But Me," they examined diversity in a range of more complex ways than children often get to ponder with adults, from the obvious differences in race and sex to the challenges of being physically handicapped.

Says Fink, "I think our goal for a lot of the work we've done over the last 10 years has been to become catalysts to make it easier for kids and parents to discuss both interesting and difficult topics, simultaneously mixing into it enough fun and humor that when you're done listening to one of these projects, you don't feel like you've been bludgeoned to death with lessons."

They delightfully reversed the current in 1995's "Parent's Home Companion," in which they offered children a way in to understanding the day-to-day issues their parents face. They recently completely a gorgeous three-CD series of songs about bedtime and the nighttime issues that every family faces.

It follows in the wake of Kahn's delightful and hugely influential "Bedtimes and Bad Times," in which he took a political songwriter's populist passion to understanding the eternal power struggle between kids and parents with keenly empathetic anthems like "One More Glass of Water" and "No More Bedtimes."

A vibrant, diverse and musically inviting marketplace has grown up with the family music movement, but it remains so far beneath the radar of mainstream media that when one of its acolytes - as Zanes is proud to regard himself - noses above that radar, his work is seen as a revelation. That attention is good news, of course, but troubling when compared to the way Fink & Marxer, with five Grammy nods for their family music, and McCutcheon, also with five, are consistently ignored for their lifetime of work in both family and general adult music.

In this context, the story of how Zanes became the chic darling of children's music is both revealing and troubling. A lifelong folk fan, when he became a father, he was disgusted with most of what he found in the children's music record bins of the record stores near his home in Brooklyn, NY.

"I was really excited to get music my daughter and I could listen to together," he says. "What I found all felt very corporate, tied into a lot of movies and TV shows. And it all sounded like it was made in a studio; I would hear the digital reverb, all the sound-effects and gimmicks. What I had really responded to when I listen to folk music as a kid was that I heard people in a room playing music, and I could picture myself right in there with them.

"That's what I've been trying to capture in my CDs. For me, it was just a natural extension of those old Folkways records I grew up listening to, which is an organic, stripped-down sound of people in a room having a good time making music together. So there's no effects, no reverbs or this or that. Not that anybody seems to notice."

As a lifelong folk fan, he was easily able to trace the trail from those old records to the work of contemporary family artists, and he came to love the non-patronizing, musically sophisticated approach pioneered by McCutcheon, Fink & Marxer, Tom Chapin, and English singer David Jones ("Widdecombe Fair," Jones's delightful traditional children's record with guitarist Bill Shute, has just been re-released as the first non-Zanes title on his Festival Five Records).

Zanes stresses that he would like nothing better than to be seen as following in the same family fields first charted by those artists, but that's not the kind of name-dropping calculated to excite the attention of Rolling Stone and Entertainment Weekly.

How that happened is that he wanted to put his own children's music in front of audiences, and asked a friend who owned a toney new Chelsea restaurant called The Park if he could do a Sunday afternoon residency. As word spread, Manhattan's literati and glitterati began to bring their kids to the shows, including Susan Sarandon, Tim Robbins, Tea Leoni, David Duchovny, Stella McCartney, and Gwyneth Paltrow.

That got the media's attention. He grumbles that media interviews too often seem to begin and end with the names of the stars who came to those shows, but he is of course, grateful for the momentum that attention gave his music.

But here is the part of the story that is never told. These family shows were dyed-in-the-wool, in-your-face folk music hootenannies. Each week, there was a special theme. One week it was Woody Guthrie, the next, Lead Belly. They would play that artist's songs, and folk songs sung by them, talk about their life and times, and even get kids drawing pictures of them between sets.

"To me, that was the big thing about all this," Zanes says, "getting to pass all this music on. But if Tea Leoni's at the show doing the Hokey-Pokey, that's what the media is going to walk away with; not that it was Woody Guthrie Day."

Everyone tries to be very philosophical about this, but the sad fact is that, once again, a bona fide folk music movement is being recognized - and highly lauded - without folk music being given any credit for creating it. The artists who shared in that creation are not mentioned anywhere for their pioneering roles, much less for the vibrant work they continue to create.

Despite his loud proclamations to the contrary, Zanes is consistently portrayed by mainstream media as having figured this out all by himself, and his constant references to the folk tradition mentioned in passing, if at all.

"I can see where it would be frustrating," says Zanes. "If you see the New York Times Magazine article about me, it's as if I'd come up with a new formula that had never been done before. And I'm doing exactly what people like John McCutcheon, Fink and Marxer, Tom Chapin, and David Jones were doing before I came along - and doing very well."

Fink says, "We are at a time when there is, for some reason, a great deal of interest among non-folkies to do children's or family recordings. As we've read in more than one newspaper interview with pop crossover artists, they say, 'Well, I had children, and it was so hard to find anything worth listening to that i just had to create something myself.' Basically, what that tells me is that they didn't look very hard. And lot of this pop crossover family music is not being made by artists who've really been in the trenches, performing for parents and kids to find out what they are thinking about, worrying about, caring about. Their market is really their grownup fans who have kids, and I'm not convinced the kids themselves particularly care for the music."

"It would be kind of like Marcy and me saying, 'Well, let's do our Top-10 hit now.' Doing that is outside where our roots are. Of course, that doesn't mean you can't plant those roots and end up making good and useful music for families, which is exactly what people like Dan Zanes and Ralph Covert have done. But they planted those roots by really doing it from the inside out, caring about how this music intersects with children and adults. And you never hear people like that say, 'Oh, there's nothing out there.' Because they've taken the time to find it."

This media indifference to the important work folk music has done over the years is, of course, nothing new to McCutcheon.

"Part of me sees it with a bit of resignation," he says quietly. "We are dealing with the music business here, which is the absolute paragon of capitalism. It eats its young; it chews up the latest thing, spits it out and says, 'What's next?' So yeah, there's going to be the People Magazine trailer on something, quickly moving on to other trends, and then 10 years later, identify the same thing, but see it again only through the prism of the personality involved, not as part of an ongoing cultural movement. That's just the way capitalism works in this country. But I do believe that, inch by inch, we move the conversation forward."

"The organizer in me says that true change comes from the bottom up, not People Magazine on down. And the ratio of good music to garbage in the family music world is very different now than it was 20 years ago, when 'Howdjadoo' came out. It was lonely back then; it's much less so now."

Originally appeared in Sing Out! The Folk Music Magazine.

Just how he is doing this may surprise longtime folk fans. His recipe for hipness is stripped-down, acoustic covers of American folk standards like "Polly Wolly Doodle," "Rock Island Line," "Skip to My Lou," Wabash Cannonball," "We Shall Not Be Moved" and the always chichi "Washington at Valley Forge."

While his records are delightful in their musical friskiness and utter lack of condescension or perky pretension, they nestle warmly into a long line of folk albums released since the evolution of the family music movement in the late 1970s. The approach is strikingly similar to that taken by such family music pioneers as John McCutcheon, Cathy Fink & Marcy Marxer, Tom Chapin, Tom Paxton, and Sally Rogers.

Zanes knows this; he insists that he is not reinventing the children's music wheel, as so many pop pundits claim, but proudly standing on the shoulders of a long tradition of folk music for children and families. He constantly mentions Ruth Crawford Seeger's groundbreaking book, "American Folk Songs for Children" as a seminal influence, not only for repertoire, but for her deep understanding of how children interact with music. Lead Belly's huge influence on Zanes is proclaimed in the third sentence of his publicity bio, and he constantly cites American folk music as the bedrock of his musical voice and vision.

Yet to hear the mainstream press tell it, what he is doing is something utterly new, edgy and unprecedented in its urbane hipness. While Zanes is understandably grateful for the media buzz that has propelled him from Manhattan restaurant performer to national children's star, he is both disappointed and mystified that the mainstream press does not see his work the way he does, following in the footsteps of a long line of folk music for children; and more precisely, the family music movement that created music not for children alone, but for whole families to enjoy together.

Zanes, a former rock star with the Del Fuegos, says, "I know if I had been reading some of the things people wrote about my music - somebody making rock'n'roll for kids - I would just be running in the other direction, because kids get plenty of that. And I don't know if what I'm making has anything to do with rock'n'roll. For me, I feel like where my music is going is towards family music more than children's music. I keep getting this idea that there's this music out that there that is really for everybody; this space where the music can exist and be fun for everybody, without losing the kids along the way. I really believe in that shared experience."

His latest album, "House Party," on his own Festival Five Records, is a merry essay on the joys of social music, deliberately designed to feel like it's roaming from room to room in a big, musical house party. The sound is spare, frisky and acoustic.

One reason his music has such a hip cache is that he invites pop and rock stars to join him on his records. On his first family album, "Rocket Ship Beach," he sang "Polly Wolly Doodle" with Sheryl Crow, and "Erie Canal" was given a deliciously droll reading by Suzanne Vega. On "House Party," he is joined by Bob Weir, Debbie Harry, and African star Angelique Kidjo, singing an achingly gentle "Jamaica Farewell."

He has never put together collections of songs exclusively meant for children. This was among the first things he learned from Ruth Seeger's book, and from the approach to family music pioneered by her stepson Pete, Woody Guthrie, Ella Jenkins, and Lead Belly. They shared adult songs with kids, treated with fun-loving introductions, and opportunities to participate. The roots to the recent family music movement lie in the classic children's recordings these artists made for Folkways in the 1940s and '50s.

According to Cathy Fink, among the most influential artists and thinkers in that movement, Pete Seeger's passion to include everyone in his music cast a rich shadow over the current crop of family artists.

"Why? Because one of Pete's greatest talents is involving everybody, getting everybody to sing and making them feel that this is our music," she says. "This is not me doing something for you; this is something we can do together."

To trace the recent roots of this folk-fueled subgenre of family music, though, you need to see what a hardscrabble, grassroots world folk music was in the 1970s, after the last spurts of the great commercial revival of the '60s had fizzled. What circuit there was for the few folk artists who toured then, including Fink and John McCutcheon, was small and intensely localized. There was no national media source for exposing folk artists to audiences, only a few small, local public radio shows.

According to Fink and McCutcheon, much of the thinking that inspired the family music movement was purely practical. Audiences were small and cultivated in highly personal ways in those days. Fan bases were literally built fan by fan, because gigs were so few and far between. Success in one venue meant absolutely nothing in the next town. Artists wanted to maximize every opportunity to expose their music to new fans, but at the same time, never wanted to give a performance everyone might not enjoy.

"By my own example," says Fink, "back in the '70s, when I would perform for folk clubs, I said to them, 'Well, if I'm doing a Friday show, maybe we should look at putting me in a school program during the day, doing something for the kids. Maybe then the kids would get interested in coming to the evening concert, and tell their parents.' And many of these venues started hosting Saturday family concerts."

Immediately, though, these folk performers realized they were playing to adults as well as kids in their children's shows. Every chance to expose folk music to audiences, particularly new audiences, was precious; and nobody wanted to put adults through a grueling experience listening to numb-headed kiddy ditties. Following the Seeger standard, artists consciously designed their programs to please everyone who was there.

Around that time, Canadian children's performer Raffi began getting exactly the same media buzz Zanes is getting today. His collections of songs, while aimed at kids, were produced with beautiful, state-of-the-art studio production. Kids loved his non-patronizing way of singing about their lives, and parents were deeply grateful that his music was so enjoyable for them to listen to - in stark contrast to the increasingly gimmicky, sound-effects-laden drivel produced by mainstream pop.

If you can point to a single moment when the modern family music movement was born, it would be 1983, with the release of John McCutcheon's groundbreaking children's album "Howjadoo." Like Raffi's recordings, it was superbly produced, the most expensive album the Appalachian folk singer-songwriter had ever made. But it s influence lay even more in how he conceived the album.

"To boil down all my thinking about 'Howjadoo,'" McCutcheon says, "the basic criteria was that I wanted this to be the album that would settle the argument in the car about what everybody was going to listen to. I wanted it to be something the kids could really enjoy, and not just be enduring for mom and dad - and vice versa. This was going to be something the whole family would enjoy."

When he did interviews following the album's release, he began referring to it as a family music album, not a children's music album. Then he would stress the differences, echoing similar changes happening throughout the folk world in its approach to performing for children. Popular performers like Fink, Sally Rogers, Tom Paxton, Tom Chapin and Bill Harley were also stressing that their shows were meant for whole families, not just for kids to clap along to and parents to patiently endure.

Fink sees a long, slow, almost organic curve in the development of this thinking. "To tell you the truth," she says, "I think we always recognized that we were getting a family audience, knowing that kids don't just get dropped off at these shows and picked up an hour later. But because of who we were as folk performers, we have this desire to connect with and interact with everybody in our audiences. We want to reach them all."

Around this time, daytime children's concerts throughout the folk world began being billed as family concerts, and the difference stressed to media, performers and presenters. For the first time, people in the folk world began to realize there was something important happening here, a genuine movement towards a new way of perceiving and presenting culture for kids and parents.

"The way the folk music community tends to work, in my opinion," says McCutcheon, "is that things really do percolate up from the grassroots. What I saw happening is that those of us who were very specific about saying 'Trust us, you'll have more people come if you call it a family concert' were drawing larger audiences, so the next time someone come through, the promoter would say, 'Let's call it a family concert.'"

These folk artists were already moving on to what, in retrospect, was the inevitable next step: creating music that explored issues whole families face together. Again, this happened simultaneously throughout the folk circuit in the '80s, but nowhere was its influence felt more than in conversations between McCutcheon and his best friend, renowned political songwriter Si Kahn.

They began looking for song ideas, talking about children's music in a radical new way. As McCutcheon put it, they didn't want to be "generational imperialists," but to break down the barricades between children's and parent's repertoires.

"When a kid loses his first tooth, for example," McCutcheon says, "It's a big deal for the whole family. It was fun as writers to present ourselves with the challenge of writing songs that had multiple portals for different people, but the common ground of experiences families share together."

As a true folk troubadour, McCutcheon was also listening to his fans. At their request, he wrote "Happy Adoption Day," which deepened his thinking about providing a musical soundtrack for modern families, what he calls "a liturgy for daily life."

One day, seeking song ideas, McCutcheon and Kahn leafed through a calendar looking for occasions that involved whole families: holidays, the first day of school, the first snowfall, the last day of school, baseball's opening day, fishing season, and walking-through-the-woods time.

The result was the friendly '90s epic most often called McCutcheon's Seasons Cycle, four Rounder albums exploring the passing of the year in the lives of American families. Mostly co-written with Kahn, the songs explore everyday themes like "New Kid in School," "Halloween," "World Series," "Labor Day," "The Flu," "Hot Chocolate," "Going to the Prom," "Junk Mail," "Frog on a Log," "Mud," "Ice Cream Man," and "Riding My Bike." In all of them, the goal was to offer these experiences from every aspect of the family experience.

"The aim was not for crossover appeal," McCutcheon says, "but for a completely shared repertoire."

Another milestone in the evolution of family music was a series of theme recordings made by Cathy Fink and her partner Marcy Marxer, beginning in 1993 with Rounder's "Help Yourself."

"The first three family albums Marcy and I did were still being called kids music, although the production values were clearly meant to be appreciated by parents," Fink says. "Then we began to look at where the holes were. What songs would actually be useful at this point?"

"Help Yourself" focused on issues of safety and self-esteem. The songs were still aimed at kids, but in ways that made them useful, fun tools for parents and teachers to discuss important issues with children. In "Nobody Else But Me," they examined diversity in a range of more complex ways than children often get to ponder with adults, from the obvious differences in race and sex to the challenges of being physically handicapped.

Says Fink, "I think our goal for a lot of the work we've done over the last 10 years has been to become catalysts to make it easier for kids and parents to discuss both interesting and difficult topics, simultaneously mixing into it enough fun and humor that when you're done listening to one of these projects, you don't feel like you've been bludgeoned to death with lessons."

They delightfully reversed the current in 1995's "Parent's Home Companion," in which they offered children a way in to understanding the day-to-day issues their parents face. They recently completely a gorgeous three-CD series of songs about bedtime and the nighttime issues that every family faces.

It follows in the wake of Kahn's delightful and hugely influential "Bedtimes and Bad Times," in which he took a political songwriter's populist passion to understanding the eternal power struggle between kids and parents with keenly empathetic anthems like "One More Glass of Water" and "No More Bedtimes."

A vibrant, diverse and musically inviting marketplace has grown up with the family music movement, but it remains so far beneath the radar of mainstream media that when one of its acolytes - as Zanes is proud to regard himself - noses above that radar, his work is seen as a revelation. That attention is good news, of course, but troubling when compared to the way Fink & Marxer, with five Grammy nods for their family music, and McCutcheon, also with five, are consistently ignored for their lifetime of work in both family and general adult music.

In this context, the story of how Zanes became the chic darling of children's music is both revealing and troubling. A lifelong folk fan, when he became a father, he was disgusted with most of what he found in the children's music record bins of the record stores near his home in Brooklyn, NY.

"I was really excited to get music my daughter and I could listen to together," he says. "What I found all felt very corporate, tied into a lot of movies and TV shows. And it all sounded like it was made in a studio; I would hear the digital reverb, all the sound-effects and gimmicks. What I had really responded to when I listen to folk music as a kid was that I heard people in a room playing music, and I could picture myself right in there with them.

"That's what I've been trying to capture in my CDs. For me, it was just a natural extension of those old Folkways records I grew up listening to, which is an organic, stripped-down sound of people in a room having a good time making music together. So there's no effects, no reverbs or this or that. Not that anybody seems to notice."

As a lifelong folk fan, he was easily able to trace the trail from those old records to the work of contemporary family artists, and he came to love the non-patronizing, musically sophisticated approach pioneered by McCutcheon, Fink & Marxer, Tom Chapin, and English singer David Jones ("Widdecombe Fair," Jones's delightful traditional children's record with guitarist Bill Shute, has just been re-released as the first non-Zanes title on his Festival Five Records).

Zanes stresses that he would like nothing better than to be seen as following in the same family fields first charted by those artists, but that's not the kind of name-dropping calculated to excite the attention of Rolling Stone and Entertainment Weekly.

How that happened is that he wanted to put his own children's music in front of audiences, and asked a friend who owned a toney new Chelsea restaurant called The Park if he could do a Sunday afternoon residency. As word spread, Manhattan's literati and glitterati began to bring their kids to the shows, including Susan Sarandon, Tim Robbins, Tea Leoni, David Duchovny, Stella McCartney, and Gwyneth Paltrow.

That got the media's attention. He grumbles that media interviews too often seem to begin and end with the names of the stars who came to those shows, but he is of course, grateful for the momentum that attention gave his music.

But here is the part of the story that is never told. These family shows were dyed-in-the-wool, in-your-face folk music hootenannies. Each week, there was a special theme. One week it was Woody Guthrie, the next, Lead Belly. They would play that artist's songs, and folk songs sung by them, talk about their life and times, and even get kids drawing pictures of them between sets.

"To me, that was the big thing about all this," Zanes says, "getting to pass all this music on. But if Tea Leoni's at the show doing the Hokey-Pokey, that's what the media is going to walk away with; not that it was Woody Guthrie Day."

Everyone tries to be very philosophical about this, but the sad fact is that, once again, a bona fide folk music movement is being recognized - and highly lauded - without folk music being given any credit for creating it. The artists who shared in that creation are not mentioned anywhere for their pioneering roles, much less for the vibrant work they continue to create.

Despite his loud proclamations to the contrary, Zanes is consistently portrayed by mainstream media as having figured this out all by himself, and his constant references to the folk tradition mentioned in passing, if at all.

"I can see where it would be frustrating," says Zanes. "If you see the New York Times Magazine article about me, it's as if I'd come up with a new formula that had never been done before. And I'm doing exactly what people like John McCutcheon, Fink and Marxer, Tom Chapin, and David Jones were doing before I came along - and doing very well."

Fink says, "We are at a time when there is, for some reason, a great deal of interest among non-folkies to do children's or family recordings. As we've read in more than one newspaper interview with pop crossover artists, they say, 'Well, I had children, and it was so hard to find anything worth listening to that i just had to create something myself.' Basically, what that tells me is that they didn't look very hard. And lot of this pop crossover family music is not being made by artists who've really been in the trenches, performing for parents and kids to find out what they are thinking about, worrying about, caring about. Their market is really their grownup fans who have kids, and I'm not convinced the kids themselves particularly care for the music."

"It would be kind of like Marcy and me saying, 'Well, let's do our Top-10 hit now.' Doing that is outside where our roots are. Of course, that doesn't mean you can't plant those roots and end up making good and useful music for families, which is exactly what people like Dan Zanes and Ralph Covert have done. But they planted those roots by really doing it from the inside out, caring about how this music intersects with children and adults. And you never hear people like that say, 'Oh, there's nothing out there.' Because they've taken the time to find it."

This media indifference to the important work folk music has done over the years is, of course, nothing new to McCutcheon.

"Part of me sees it with a bit of resignation," he says quietly. "We are dealing with the music business here, which is the absolute paragon of capitalism. It eats its young; it chews up the latest thing, spits it out and says, 'What's next?' So yeah, there's going to be the People Magazine trailer on something, quickly moving on to other trends, and then 10 years later, identify the same thing, but see it again only through the prism of the personality involved, not as part of an ongoing cultural movement. That's just the way capitalism works in this country. But I do believe that, inch by inch, we move the conversation forward."

"The organizer in me says that true change comes from the bottom up, not People Magazine on down. And the ratio of good music to garbage in the family music world is very different now than it was 20 years ago, when 'Howdjadoo' came out. It was lonely back then; it's much less so now."

Originally appeared in Sing Out! The Folk Music Magazine.