Articles

Old Time Music: A Brief History

Monday, May 14, 2012

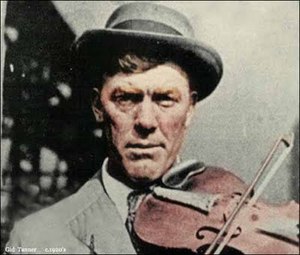

Old Time Pioneer Gid Tanner

Part 1, Mountain Journey

Author’s Note. In 2004, Rounder Records released two CDs tracing the recorded history of old-time music, the term Southern rural people used to describe their traditional folk songs, tunes, and ballads. They asked me to write the liner notes, and what resulted was something of a primer for old-time music, and the culture from which it grew. I’ve combined both sets of liner notes here, to form a continuing narrative of old-time's evolution from the dawn of the commercial music industry to modern times, from Gid Tanner to Dirk Powell (both pictured above), Ola Belle Reed to Alison Krauss (both pictured below). At the end, there are brief biographies of every artist included in the two-volume anthology. One reason I enjoy writing liner notes is that I always learn so much, directly from the artists whose story is being told. Scott Alarik

Before music became an industry, before CDs or DVDs, radios or televisions, the family entertainment center was often a guitar, a banjo, or a fiddle. This music, the self-made soundtrack to the lives of ordinary people, became called folk music, from a colloquial term for the poor and working classes.

Before music became an industry, before CDs or DVDs, radios or televisions, the family entertainment center was often a guitar, a banjo, or a fiddle. This music, the self-made soundtrack to the lives of ordinary people, became called folk music, from a colloquial term for the poor and working classes.

In the remote southern mountains, however, where these social musical traditions thrived well into the 20th century, the folk had their own name for the music they made to accompany their daily lives. They called it old-time music.

It is, by form and function, starkly different from today’s commercial pop music. There is music for all the moments in people’s lives, from courting to dying, playing with children to working in the fields and mines. There are songs of adorable innocence and world-weary anguish, silly mischief and populist rage, seduction and heartbreak, ennobling hope and utter despair. What all the music shares is a visceral connection to the way real people live their lives.

Today, that realness is drawing people to old-time music more than at any time since the commercial folk revival of the 1960s. But this is no fleeting fad for Rounder Records. The Cambridge, MA., company was founded in large part to document the vanishing traditions of southern mountain music. It has since grown into the world’s most prolific and successful folk music label, but retains a special fondness for the raw splendor of southern mountain music.

“Mountain Journey” is the first of two CDs compiled from the Rounder archives as samplers of old-time music. This disc travels the backroads of the music’s roots. Though many crucial masters are here, it is not presented as an encyclopedia of stars or tunes, but more as a landscape, scanning the vistas of the music and how it actually lived among the people who created it.

Many people today are confused about the difference between old-time music and bluegrass. They are perfectly right to be confused, since bluegrass has, at its core, the repertoire of old-time music. Bluegrass is, in fact, a relatively recent offshoot of old-time music, growing from its ancient soil little more than 60 years ago.

Performer-archivist-collector Mike Seeger has done as much as anyone to popularize, preserve, and document old-time music. He believes the line between old-time and bluegrass is best observed by listening to what makes bluegrass unique: its tight, ensemble sound and driving cadence, fueled by the Earl Scruggs three-fingered banjo style, downbeat bass beat, and the off-beat mandolin rhythm chops pioneered by Bill Monroe.

Though many of the tunes on this CD are also quick and propulsive, little of that unique bluegrass groove, or its trademark high, lonesome harmonies, is heard. But listen closely, and you will hear the roots of all those things.

Seeger’s mother, the influential musicologist and composer Ruth Crawford Seeger, properly described old-time as “a folk name for folk music.” It describes all the traditional music embraced by southern mountain folk.

“Bluegrass is one kind of music,” Mike Seeger says, “and old-time is many kinds of music. Bluegrass is a music that grew out of both black and white southern traditional music. And it evolved primarily as a performance music, while old-time music, at its heart, is a social music, a folk form in the oldest and purest sense of the term.”

Hazel Dickens is one of the most influential living singers of old-time music. Born in Mercer County, West Virginia, she grew up around the last echoes of the purely social old-time traditions, before records and radios offered new, impersonal ways to hear music. While she was as likely to learn a song off the radio as from her singing parents, she saw music still made to accompany the lives of her community.

She particularly noticed how completely the old music punctuated the lives of her parents. Her father walked 15 miles across the mountains to court her mother, after which they would sing and play music all night long.

“The music permeated everything they did socially in those days,” Dickens says, “because there was nothing else to do but go to church and play music. Of course, music was a big part of church, too.”

Most of the quickstep fiddle and banjo tunes were, at heart, dance tunes, many with melodic roots in Ireland, Scotland, and England. They would be played as people danced, either at community dances or house parties. Frisky ditties called “frolic songs,” such as “Cripple Creek,” were often danced to as well.

The call to the dance is vibrantly heard on J.P. Fraley’s classic rendition of “Wild Rose of the Mountain.” By contrast, Buddy Thomas’ “Sweet Sunny South” is done more in the expressive style of the air, or instrumental tune meant for listening.

Ballads, or story-songs, laments, and love songs would be shared in evenings, around the fire or potbellied stove. They were the night’s entertainment, often igniting spirited discussions about their meaning and lessons.

That’s also when a wistful song like “Pretty Bird,” which Dickens wrote in the old style, would most likely be sung. The powerful dissonance of close mountain harmonies is wonderfully heard in her duet with Ginny Hawker on the aching populist lament, “Times Are Not What they Used to Be.”

Seeger says these songs were used at other times as well: “Ballads, love songs, and frolic songs would also be sung during breaks from the workday, at the end of a row in the fields. Or when it was ‘layin’-by’ time, the slow times like winter. Also at night when the kids were going to sleep, or in the morning when mom was cooking over the woodstove.”

The vocal traditions originated as a chiefly unaccompanied style, later adapted to fit the accompaniment of banjo and guitar. In the opening track, legendary North Carolina singer Ola Belle Reed offers a gorgeous essay in the evolution of the old-time vocal style. While her guitar tinkles sparely, she begins in the old, unaccompanied style, her cadence shaped by the emotion of the lyric. Then her guitar takes the lead, the tempo tightens, and her phrasing compresses to suit the guitar. Not better, not worse; just different.

Though old-time describes primarily the folk music of the white rural south, its intermingling with African-American tradition was a rich stream that flowed between both cultures. Slaves developed the banjo from stringed instruments in their native Africa, but it was played as a white folk instrument by the early 1700s. Similarly, blacks picked up white instrumentals (called tunes) and vocal songs, adding their own distinctive stamp, which, in turn, found its way back into the way whites performed the music.

African-American old-time and blues musician Etta Baker proves how vibrantly white traditions existed in her community in her coy, sprightly duet with Seeger on “Cripple Creek.” Similarly, the black nuance we have come to call the blues influence, though it actually predates the blues, is hauntingly evident in old-time giant Doc Watson’s singing of “And Am I Born to Die?”

Church dominated the lives of most mountain people. There were liturgical hymns sung mainly in church, but also a vast repertoire of sacred songs that were heard at all times. Much of the liturgical repertoire was spread in hymnals called “shape-note books,” because of a clever iconic system developed in the 1800s to allow illiterate people to read musical notation. The simple, sturdy harmonies allowed for much freedom of emotional expression.

One branch of that tradition is called Sacred Harp, after one of the most popular of these 19th-century hymnals. It can still heard at rural churches in Georgia and Alabama, as captured in “The Traveller.”

New music technologies, beginning with the first radios and phonographs, gradually displaced the old traditions. But even as they faded, they were being documented, recorded, and taken up by modern folk artists like Seeger. During the ‘60s folk revival, Seeger’s band the New Lost City Ramblers popularized old-time music throughout the country, creating legions of new fans at college campuses and coffeehouses.

Savvy professional performers with old-time roots, such as Doc Watson and Hazel Dickens, became national stars. Just as importantly, communities of nonprofessional musicians and folk dancers sprang up all over the country, who eagerly embraced old-time music as the social form it was at heart. Old-time pickin’ parties, festivals, fiddle and banjo camps, and folk dances became cultishly popular, and actually grew as the commercial folk revival declined.

Dickens watched the transformation of the music brought on by the commercial folk revival, and even earlier by the ensemble rigors of bluegrass.

“As the music got heard on the radio more, and performed by professional musicians,” she recalls, “it got more polished, slicker. I don’t mean the songs themselves changed, but people became more aware that it was not parlor music anymore, the way we’d always known it. We’d hear people like Jim and Jesse on the radio, and their playing was so impeccable. When it gets that good, everybody feels a little challenged by it; that if they want to play it, boy, they’ve got to really step up to the plate. It wasn’t like the old raw stuff you felt you could just pull up a chair and join in with. It took some of the fun out of it.”

Thankfully, most popular old-time stars, like Seeger and Dickens, worked to ensure that the music also retained its carefree, nonprofessional identity, and became powerful allies in the social revivals of the music, which are chronicled in Volume 2 of Rounder’s old-time odyssey, “Come to the Mountain.”

“Almost every place I’ve gone to sing,” Dickens says, “there’s a social scene, pockets of people just getting together to play the music for fun, the way it’s meant to be. I don’t think people realize how many nonprofessionals there are who still play this music. There’s no way to calculate the joy it brings to people like that, people who would never think of playing the music for money, and yet they get immense pleasure from learning the songs, getting their spouse to sing a harmony. It’s stayed truer to itself that way than some other musics have, I think.”

Scott Alarik, June, 2004

Old Time Music, part 2. “Come To the Mountain”

Old-time music is the term southern folk use to describe their folk music. Long after similar traditions had faded in most parts of the country, this vibrant, self-made music - dance tunes and frolic songs, tragic ballads and wistful love songs - coninued to pass from generation to generation in remote, rural areas of the south, particularly in the mountains. Though it formed the root of both country music and bluegrass, old-time music in all its wild, folksy grace was rarely heard outside the communities that created it.

The commercial folk revival of the 1960s changed all that, exposing the music to millions of people all over the world. This CD, the companion to Rounder’s more purely traditional old-time homage “Mountain Journey,” chronicles how this uniquely southern music traveled and was transformed by the ‘60s revival; and by the string-band and folk-dance revivals that followed in its wake, and are still thriving today.

In Syracuse, New York, a kid weaned on classical music, jazz, and Broadway show tunes heard an old-timey banjo break in the 1963 Kingston Trio hit “Charlie on the MTA.” “It literally forced me to play the banjo,” Tony Trischka recalls. “I calll them the 16 notes that ruined my life.”

Around the same time, a violin prodigy in the Bronx was enrolled in the prestigious High School of Music and Art. Classmates played him obscure recordings of vintage old-time musicians. Classical music lost a promising violinist, but old-time music got itself one helluva fiddler in Jay Ungar.

This new generation of fans watched as the increasingly commercial folk revival turned away from traditional forms like old-time music. Rounder Records, from whose archives all the selections here come, was founded in 1970, its original mission to record old-time musicians the folk revival was ignoring.

In a sweet irony, the music’s lack of commercial viability became its greatest asset.

“There was the lingering notion that this music could die away,” Ungar recalls. “That was a very strong feeling among nearly all of the people who came into the music in the late ‘60s and ‘70s. There was almost an evangelical feeling about it. It seemed like it had almost died, and we wanted to make sure that never happened again.”

Free of the need to even contemplate what the commercial music industry might want of them, these new old-time musicians sought their own ways to create contemporary contexts in which the music could thrive.

This quest took two distinct, though parallel paths. The old-time revival that began in the late 1960s, and blossomed throughout the ‘70s, was like a twin-thrust engine, each power burst running on its own fuel, but serving the common goal of moving this music forward.

Savvy urban musicians like Trischka followed the cue of progressive bluegrass, reinventing the old music with modern jazz, pop, classical, rock and world beat influences.

Trischka describes this movement as a bi-coastal phenomenon. “There was the California thing with David Grisman, Darrol Anger, Mike Marhsall, and Tony Rice stretchng boundaries, combining bluegrass, western swing, jazz. But it was very organized in its way.”

“Then in New York, it was me, Kenny Kosek, Andy Statman, Stacy Phillips, and that whole crew, doing stuff that was even more out; taking klezmer and Hawaiian and jazz and rock and soul - anything we could get our hands on. Our music was a little rougher, more hell-bent-for-leather. A little more fur-bearing, you might say.”

At the same time, other musicians, like Ungar, sought ways to make this a real community music again. In 1971, with New Lost City Ramblers founder John Cohen, Ungar formed the Putnam String County Band in upstate New York. The goal was to be a concert band, but also to function as genuine village musicians, performing for local folk dances, seasonal celebrations, and other community gatherings. In fact, the playful name morphed from their original band, the Putnam County String Band, which had a slightly different cast. It played only for local dances, and refused to tour or record.

“I think many of us were quite aware that we were not from the culture that this music came from,” Ungar says. “We were trying to make our own family and community culture, and to have this music be its music. So naturally, the music changed somewhat in its form and function. We hoped we were creating a culture for this music, something we could live with for the rest of our lives, and pass on to our children.”

As traditional as their music might sound to us today, what Ungar’s band was doing was startlingly new, combining a keen knowledge of old-time traditions with a modern - and non-southern - eclecticism. The CD, for example, opens with the sweet drones of Abby Newton’s cello, heralding an entirely new ensemble approach to this music.

The music’s lack of commercial viability also inspired its devotees to develop alterntive ways to supplement their music incomes. They quickly realized they were, in fact, designing a modern equivalent to tradition itself, replicating ways for the music to pass from generation to generation. Players like Ungar and Trischka became interested in teaching, and in creating new environments for this music to be taught in the old, orally transmitted ways. Instruction cassettes and videos, music camps, and instructional workshops became important parts of their careers.

“The fiddle and banjo camps are like festivals, except you’re all learning,” Trischka says. “You get a bunch of people together who are all into the same thing, and really inculcate yourself.”

These immersion camps and workshops encourage a traditional style of learning, by ear from master players. As a result, much more than rudiments and techniques are passed along. Just as in the old days, the values and ethos of the music, the culture behind it, are passed from elders to students.

Ungar created a summer series of music and dance camps that became known as the Ashokan camps. As proof of how intense the immersion can be, his famous theme “Ashokan Farewell,” which was heard in Ken Burns’ epic documentary “The Civil War,” was written to express Ungar’s mood at the end of a particularly intimate camp week.

“The concept of marketing this music didn’t exist for us, even if we wanted to go that way, which we really didn’t,” Ungar says. “Nobody was into this music for that; it was more that you just wanted to make enough money so you could keep doing it.”

Adds his wife and current performing partner Molly Mason, “This music became your job in the community, something you do for everybody. There was no pretension that anybody was going to get rich at this, so on every level, it had a good feeling about it. It felt clean and honest.”

This movement toward teaching brought more young people into the music. It also encouraged even the most innovative artists to know more about the history of the music. Trischka may be a banjo revolutionary, but he also does shows tracing his instrument’s long history.

“As much as I’m into the progressive side, I’ve also gotten into the history,” he says, “and passing that along has become a passion for me over the years. You learn the roots of the music, and you just want to carry it on.”

In the ‘80s, a new generation, raised within this modern old-time culture, began to emerge. Unlike Ungar and Trischka, they had never known a world in which the music seemed perishable. They grew up believing it was their legacy, and they learned it in thriving musical communities, at fiddle camps, music contests, and pickin’ parties.

Alison Krauss is a prime example of this new generation. As a child, she competed in fiddle contests, and brings a lifelong immersion in traditional music into the modern musical arena.

Similarly, hot young bluesman Corey Harris is utterly at home in his provocative explorations of the African-American folk roots that begat the blues. While banked in ancient sounds, his artfully nuanced primitivism is as modern as hip-hop.

Another rising young star is 34 year-old multi-instrumentalist Dirk Powell. He first heard old-time music as a social form, played purely for fun by his grandfather. When he discovered young urban kids like himself gathering near his Ohio home for old-time jam sessions, he was hooked.

“This really seemed like a form in which you could express anything,” Powell says. “I also felt like it was totally noncommercial, in the sense that nobody was doing it with the first and foremost goal of selling records. As a teenager, you define yourself so much by the music you listen to, and at the time I was listening to punk, because it expressed a lot of things I was angry about, like how the place I lived seemed like such a big cultural vacuum. But I also knew that punk was an image that was being sold, and that was exactly what I was rebelling aginst.

“It started dawning on me that old-time music was just about the music, and a real exchange between people. That was the goal, just coming together to share something. It felt to me like this was really rebelling - not just railing against the system, but stepping completely outside of it and making music for its own sake.”

You won’t measure the real health of the old-time revival today by scanning the Billboard charts, but by the number of people picking up banjos and fiddles, and seeking out fellow pickers in neighborhood pubs, cellar coffeehouses, folk dances, and private homes. Elderly Instruments, a comprehensive folk instrument and supplies store with an international mail-order business, reports dramatic, steady increases in the sales of all folk instruments over the last few years, with a curve that’s trending only upward - even as pop record sales continue their historic decline.

Powell says, “I think of traditional music as a bottomless well; the more you take from it, the more you give to it. It’s a sustainable resource; that’s what’s so powerful about it, and why more people are listening to it and playing it today. So much of our social culture has succumbed to mass-marketing. I think a lot of American teenagers are floundering today because they’ve had all those necessary social ties pulled away from them. I was just lucky to have a grandfather who played the banjo.”

Scott Alarik, June, 2004

About the Artists, Part 1

Ola Belle Reed. Born in Asheville County, North Carolina in 1915, Reed was renowned for her earthy vocal style, clawhammer banjo, and devotion to the social heart of old time music. As a young woman, she declined an invitation to tour with Roy Acuff, feeling the the show-biz fast-lane might dampen her convivial, down-home love of the music. The hot vocal band Ollabelle is named in honor of Reed.

Bascom Lamar Lunsford. With his masterful five-string banjo playing and devotion to preserving the music, Lunsford transformed his home region of South Turkey Creek, North Carolina, into a celebrated old-time hotbed. He was a prolific collector of traditional music, and helped the world discover crucial regional artists like George Pegram and Red Parham.

Mike Seeger with Etta Baker. Seeger is the son of seminal ethnomusicologist Charles Seeger and composer Ruth Crawford Seeger, and stepbrother of folk icon Pete. As performer, folkloric collector, and archivist, he has done more to bring old time music to the world than perhaps anyone. Baker’s music was exquisitely poised where the black and white musical traditions of her native North Carolina intermingled.

George Pegram and Red Parham. Rounder Records was originally founded simply to preserve Pegram’s wonderfully raw, sweet banjo playing. Both he and singer-guitar-harmonica-player Parham were discovered by Bascom Lamar Lunsford.

Doc Watson and Gaither Carlton. No single performer did more to popularize old time music outside the south than blind North Carolina guitarist-singer Watson, who has remained a major star since the early days of the commercial folk revival. Carlton was Watson’s father-in-law.

Ginny Hawker. Born in Halifax County, Virginia, Hawker is a widely respected mountain singer first discovered by Hazel Dickens. She is married to New Lost City Ramblers alumnus Tracy Schwartz, with whom she frequently performs as a duo.

J.P. Fraley. A renowned master of the strong-bowed, vibrato-rich fiddle style of Eastern Kentucky, Jesse Presley Fraley often performed with his wife Annadeene. Together, they founded the popular Fraley Family Music Festival.

Buddy Thomas. Equally at home with brisk bluegrass dance tunes or melancholy mountain airs, Thomas was regarded as one of the last and finest exponents of the emotive fiddle style of northeastern Kentucky.

Sacred Harp singers of Georgia and Alabama. This gathering of nonprofessional shape-note singers from the Sacred Harp style popular in Georgia and Alabama was assembled especially for this 1977 recording by Hugh McGraw. “Traveller” was sung just as it would be in church.

Hazel Dickens. Born in Mercer County, West Virginia, Dickens is arguably the most important female old time singer and songwriter of the last 40 years. Her haunting vocal directness, populist urgency, and feminist fire made her popular both with both traditional and women’s music audiences, and her songs have been recorded by many modern artists, including Dolly Parton, Laurie Lewis, and Hot Rize.

Connie and Babe and the Backwoods Boys. Regional radio and recording stars around their Tennessee homes in the 1950s, their music is poised at the precise crossroads where old time music blossomed into bluegrass.

Dry Branch Fire Squad. With one foot firmly in the soil of old time music, the other tapping away to bluegrass, this band has remained in the front lines of the string band revival for nearly 30 years. Their stage shows are renowned for their musical vibrancy and smart country humor.

Hazel Dickens and Alice Gerard. Dickens first came to national prominence in a duo with Seattle native Gerard, who brought an urban polish to Dicken’s pure mountain style. They first performed in 1962 at a fiddler’s contest in Galax, Virginia.

Fuzzy Mountain String Band. The band grew out of the social music scene in Durham, North Carolina. Fondly dubbed “the Fuzzies,” the shaggy sextet formed in 1967, and is credited with helping translate the informal fun of an old-time pickin’ party to the concert stage.

Blue Sky Boys. Brothers Earl and Bill Bolick were contemporaries of the Monroe and Stanley brothers, but resisted their driving, bluegrass pulse. Their straightforward, spacious style, close, sweet harmonies, and subdued emotionalism are models of the classic mountain balladry from which both bluegrass and modern country music evolved.

Ralph Blizzard and the New Southern Ramblers. Blizzard championed a Tennessee fiddle style he called “Appalachian Mountain Longbow.” He was a regional star as a young man, then left music to support his family. He picked up the fiddle 25 years later to became revered as a traditional master and teacher.

Dirk Powell with Tim O’Brien. As solo artist and with his influential band Hot Rize, O’Brien has been in the vanguard of progressive bluegrass for over 20 years. Powell is a dynamic young multi-instrumentalist, equally at home with pure Appalachian tradition or recording with pop stars like Sting and Jewel. His banjo was heard in the the films “Cold Mountain” and “Bamboozled.”

About the Artists, Part 2

Putnam String County Band. Among the most important bands in fomenting the string-band and folk dance revivals, the upstate New York quartet was founded in 1971 by New Lost City Ramblers’ member John Cohen, Jay Ungar, his then-wife Lyndon Ungar, and pioneering folk cellist Abby Newton. Jay and Lyn’s daughter Ruth Ungar is the fiddler of the hot neo-trad band The Mammals.

Dirk Powell. Powell is a dynamic multi-instrumentalist, equally at home with pure Appalachian tradition or recording with pop stars like Sting and Jewel. His banjo playing was heard in the the films “Cold Mountain” and “Bamboozled.”

Mac Benford & the Woodshed All-Stars featuring Marie Burns. Benford was a founding member of the Highwoods String Band, arguably the most influential old-time string band of the ‘70s. Thanks in large part to Burns’ sultry vocals and songwriting, this band paved the way in fusing old-time to modern folk-pop.

Corey Harris. Colorado native Harris is a leader in the recent revival of blues among young African-Americans, and starred in Martin Scorcese’s acclaimed documentary “Feel Like Going Home.” He is also an important archivist and collector of neglected black traditional artists, such as the Rising Star Fife and Drum Band.

Tony Trischka with Northampton Harmony. Banjo star Bela Fleck calls Trischka “my springboard,” and compares his impact to that of Miles Davis or John Coltrane in jazz. Triscka is also an eminent banjo historian. Northampton Harmony was led by rising neotraditional star Tim Eriksen.

Jones and Leva. James Leva and Carol Elizabeth Jones were raised around string-band music. Though from New Jersey, Leva’s father performed for square dances, and Jones’ father headed the Appalachian Studies program at Kentucky’s Berea College.

Norman Blake. Blake’s spacious, elegantly melodic playing profoundly influenced the way southern folk music is played today. Raised in Georgia, he became a national star in Johnny Cash’s band in 1969, and subsequently on Bob Dylan’s “Nashville Skyline” album. Today, he performs chiefly with his cellist wife Nancy Blake.

James Bryan. The Alabama fiddler rose to prominence in Norman Blake’s Rising Fawn String Ensemble, but also performed with the Grand Ole Opry and Tennesse Ernie Ford.

Ron Block. Block plays banjo, guitar and sings with Alison Krauss + Union Station. His songs have been recorded by Krauss, Rhonda Vincent, Randy Travis, and the Cox Family.

Jay Ungar. Raised in the Bronx, Ungar became one of the architects of the northeastern string-band and folk-dance revivals, both as fiddler and with his popular music and dance camps in Ashokan, New York.

Rory Block and Lee Berg. In 1972, a gathering of acoustic stars in Woodstock, New York, made the hugely popular “Music from Mud Acres” records, combining the jamming vibe of an old-time pickin’ party with stellar musicianship. Block is among the most popular modern performers of folk blues.

Dry Branch Fire Squad. With one foot firmly in the soil of old time music, the other tapping away to bluegrass, this band has remained in the front lines of the string band revival for nearly 30 years. Their shows are renowned for their musical vibrancy and smart country humor.

Tony Furtado. Among the most innovative and respected of the “young turks” revolutionizing the way the banjo is played today, Furtado is also a great slide guitar player.

Riley Baugus. A North Carolina native, Baugus was reared on old-time music, learning to play from neighbors such as traditional masters Tommy Jarrell and Robert Sykes. He is also a banjo maker and blacksmith.

Fiddle Fever. Among the most innovative of the string-band revival bands, its members included Jay Ungar, Molly Mason, and Matt Glaser, chair of the string department at Berklee College of Music, and founder of the similarly inventive Wayfaring Strangers.

Lynn Morris. Among the most prominent female stars in bluegrass today, Morris was born in Texas, and twice won the National Banjo Championship. She has also won three Vocalist of the Year Awards from the International Bluegrass Music Association.

John Sebastian and Paul Butterfield. Two of the stars who took part in the Mud Acres sessions in Woodstock, NY. Sebastian founded the ‘60s folk-rock band the Lovin’ Spoonful. Butterfield’s eponymous ‘60s band fused Chicago blues to modern rock, and introduced the world to guitar legend Mike Bloomfield.

Alison Krauss + Union Station. Krauss is on her way to becoming the greatest crossover star in bluegrass history. She cut her teeth winnning fiddle contests as a child, and made her first record for Rounder in 1987, at 15. Among the finest and most influential singers anywhere in American music, she has already won more Grammies than any female artist in history (14).

Author’s Note. In 2004, Rounder Records released two CDs tracing the recorded history of old-time music, the term Southern rural people used to describe their traditional folk songs, tunes, and ballads. What resulted was a primer for old-time music, and the culture from which it grew. I’ve combined both sets of liner notes here, to from a continuing narrative of old-times evolution from the dawn of the commercial music industry to modern times, from Gid Tanner to Dirk Powell, Hazel Dickens to Alison Krauss. At the end, there are brief biographies of every artist included in the two-volume anthology. One reason I enjoy writing liner notes is that I always learn so much, directly from the artists whose story is being told. Scott Alarik

Before music became an industry, before CDs or DVDs, radios or televisions, the family entertainment center was often a guitar, a banjo, or a fiddle. This music, the self-made soundtrack to the lives of ordinary people, became called folk music, from a colloquial term for the poor and working classes.

In the remote southern mountains, however, where these social musical traditions thrived well into the 20th century, the folk had their own name for the music they made to accompany their daily lives. They called it old-time music.

It is, by form and function, starkly different from today’s commercial pop music. There is music for all the moments in people’s lives, from courting to dying, playing with children to working in the fields and mines. There are songs of adorable innocence and world-weary anguish, silly mischief and populist rage, seduction and heartbreak, ennobling hope and utter despair. What all the music shares is a visceral connection to the way real people live their lives.

Today, that realness is drawing people to old-time music more than at any time since the commercial folk revival of the 1960s. But this is no fleeting fad for Rounder Records. The Cambridge, MA., company was founded in large part to document the vanishing traditions of southern mountain music. It has since grown into the world’s most prolific and successful folk music label, but retains a special fondness for the raw splendor of southern mountain music.

“Mountain Journey” is the first of two CDs compiled from the Rounder archives as samplers of old-time music. This disc travels the backroads of the music’s roots. Though many crucial masters are here, it is not presented as an encyclopedia of stars or tunes, but more as a landscape, scanning the vistas of the music and how it actually lived among the people who created it.

Many people today are confused about the difference between old-time music and bluegrass. They are perfectly right to be confused, since bluegrass has, at its core, the repertoire of old-time music. Bluegrass is, in fact, a relatively recent offshoot of old-time music, growing from its ancient soil little more than 60 years ago.

Performer-archivist-collector Mike Seeger has done as much as anyone to popularize, preserve, and document old-time music. He believes the line between old-time and bluegrass is best observed by listening to what makes bluegrass unique: its tight, ensemble sound and driving cadence, fueled by the Earl Scruggs three-fingered banjo style, downbeat bass beat, and the off-beat mandolin rhythm chops pioneered by Bill Monroe.

Though many of the tunes on this CD are also quick and propulsive, little of that unique bluegrass groove, or its trademark high, lonesome harmonies, is heard. But listen closely, and you will hear the roots of all those things.

Seeger’s mother, the influential musicologist and composer Ruth Crawford Seeger, properly described old-time as “a folk name for folk music.” It describes all the traditional music embraced by southern mountain folk.

“Bluegrass is one kind of music,” Mike Seeger says, “and old-time is many kinds of music. Bluegrass is a music that grew out of both black and white southern traditional music. And it evolved primarily as a performance music, while old-time music, at its heart, is a social music, a folk form in the oldest and purest sense of the term.”

Hazel Dickens is one of the most influential living singers of old-time music. Born in Mercer County, West Virginia, she grew up around the last echoes of the purely social old-time traditions, before records and radios offered new, impersonal ways to hear music. While she was as likely to learn a song off the radio as from her singing parents, she saw music still made to accompany the lives of her community.

She particularly noticed how completely the old music punctuated the lives of her parents. Her father walked 15 miles across the mountains to court her mother, after which they would sing and play music all night long.

“The music permeated everything they did socially in those days,” Dickens says, “because there was nothing else to do but go to church and play music. Of course, music was a big part of church, too.”

Most of the quickstep fiddle and banjo tunes were, at heart, dance tunes, many with melodic roots in Ireland, Scotland, and England. They would be played as people danced, either at community dances or house parties. Frisky ditties called “frolic songs,” such as “Cripple Creek,” were often danced to as well.

The call to the dance is vibrantly heard on J.P. Fraley’s classic rendition of “Wild Rose of the Mountain.” By contrast, Buddy Thomas’ “Sweet Sunny South” is done more in the expressive style of the air, or instrumental tune meant for listening.

Ballads, or story-songs, laments, and love songs would be shared in evenings, around the fire or potbellied stove. They were the night’s entertainment, often igniting spirited discussions about their meaning and lessons.

That’s also when a wistful song like “Pretty Bird,” which Dickens wrote in the old style, would most likely be sung. The powerful dissonance of close mountain harmonies is wonderfully heard in her duet with Ginny Hawker on the aching populist lament, “Times Are Not What they Used to Be.”

Seeger says these songs were used at other times as well: “Ballads, love songs, and frolic songs would also be sung during breaks from the workday, at the end of a row in the fields. Or when it was ‘layin’-by’ time, the slow times like winter. Also at night when the kids were going to sleep, or in the morning when mom was cooking over the woodstove.”

The vocal traditions originated as a chiefly unaccompanied style, later adapted to fit the accompaniment of banjo and guitar. In the opening track, legendary North Carolina singer Ola Belle Reed offers a gorgeous essay in the evolution of the old-time vocal style. While her guitar tinkles sparely, she begins in the old, unaccompanied style, her cadence shaped by the emotion of the lyric. Then her guitar takes the lead, the tempo tightens, and her phrasing compresses to suit the guitar. Not better, not worse; just different.

Though old-time describes primarily the folk music of the white rural south, its intermingling with African-American tradition was a rich stream that flowed between both cultures. Slaves developed the banjo from stringed instruments in their native Africa, but it was played as a white folk instrument by the early 1700s. Similarly, blacks picked up white instrumentals (called tunes) and vocal songs, adding their own distinctive stamp, which, in turn, found its way back into the way whites performed the music.

African-American old-time and blues musician Etta Baker proves how vibrantly white traditions existed in her community in her coy, sprightly duet with Seeger on “Cripple Creek.” Similarly, the black nuance we have come to call the blues influence, though it actually predates the blues, is hauntingly evident in old-time giant Doc Watson’s singing of “And Am I Born to Die?”

Church dominated the lives of most mountain people. There were liturgical hymns sung mainly in church, but also a vast repertoire of sacred songs that were heard at all times. Much of the liturgical repertoire was spread in hymnals called “shape-note books,” because of a clever iconic system developed in the 1800s to allow illiterate people to read musical notation. The simple, sturdy harmonies allowed for much freedom of emotional expression.

One branch of that tradition is called Sacred Harp, after one of the most popular of these 19th-century hymnals. It can still heard at rural churches in Georgia and Alabama, as captured in “The Traveller.”

New music technologies, beginning with the first radios and phonographs, gradually displaced the old traditions. But even as they faded, they were being documented, recorded, and taken up by modern folk artists like Seeger. During the ‘60s folk revival, Seeger’s band the New Lost City Ramblers popularized old-time music throughout the country, creating legions of new fans at college campuses and coffeehouses.

Savvy professional performers with old-time roots, such as Doc Watson and Hazel Dickens, became national stars. Just as importantly, communities of nonprofessional musicians and folk dancers sprang up all over the country, who eagerly embraced old-time music as the social form it was at heart. Old-time pickin’ parties, festivals, fiddle and banjo camps, and folk dances became cultishly popular, and actually grew as the commercial folk revival declined.

Dickens watched the transformation of the music brought on by the commercial folk revival, and even earlier by the ensemble rigors of bluegrass.

“As the music got heard on the radio more, and performed by professional musicians,” she recalls, “it got more polished, slicker. I don’t mean the songs themselves changed, but people became more aware that it was not parlor music anymore, the way we’d always known it. We’d hear people like Jim and Jesse on the radio, and their playing was so impeccable. When it gets that good, everybody feels a little challenged by it; that if they want to play it, boy, they’ve got to really step up to the plate. It wasn’t like the old raw stuff you felt you could just pull up a chair and join in with. It took some of the fun out of it.”

Thankfully, most popular old-time stars, like Seeger and Dickens, worked to ensure that the music also retained its carefree, nonprofessional identity, and became powerful allies in the social revivals of the music, which are chronicled in Volume 2 of Rounder’s old-time odyssey, “Come to the Mountain.”

“Almost every place I’ve gone to sing,” Dickens says, “there’s a social scene, pockets of people just getting together to play the music for fun, the way it’s meant to be. I don’t think people realize how many nonprofessionals there are who still play this music. There’s no way to calculate the joy it brings to people like that, people who would never think of playing the music for money, and yet they get immense pleasure from learning the songs, getting their spouse to sing a harmony. It’s stayed truer to itself that way than some other musics have, I think.”

Scott Alarik, June, 2004

Old Time Music, part 2. “Come To the Mountain”

Old-time music is the term southern folk use to describe their folk music. Long after similar traditions had faded in most parts of the country, this vibrant, self-made music - dance tunes and frolic songs, tragic ballads and wistful love songs - coninued to pass from generation to generation in remote, rural areas of the south, particularly in the mountains. Though it formed the root of both country music and bluegrass, old-time music in all its wild, folksy grace was rarely heard outside the communities that created it.

The commercial folk revival of the 1960s changed all that, exposing the music to millions of people all over the world. This CD, the companion to Rounder’s more purely traditional old-time homage “Mountain Journey,” chronicles how this uniquely southern music traveled and was transformed by the ‘60s revival; and by the string-band and folk-dance revivals that followed in its wake, and are still thriving today.

In Syracuse, New York, a kid weaned on classical music, jazz, and Broadway show tunes heard an old-timey banjo break in the 1963 Kingston Trio hit “Charlie on the MTA.” “It literally forced me to play the banjo,” Tony Trischka recalls. “I calll them the 16 notes that ruined my life.”

Around the same time, a violin prodigy in the Bronx was enrolled in the prestigious High School of Music and Art. Classmates played him obscure recordings of vintage old-time musicians. Classical music lost a promising violinist, but old-time music got itself one helluva fiddler in Jay Ungar.

This new generation of fans watched as the increasingly commercial folk revival turned away from traditional forms like old-time music. Rounder Records, from whose archives all the selections here come, was founded in 1970, its original mission to record old-time musicians the folk revival was ignoring.

In a sweet irony, the music’s lack of commercial viability became its greatest asset.

“There was the lingering notion that this music could die away,” Ungar recalls. “That was a very strong feeling among nearly all of the people who came into the music in the late ‘60s and ‘70s. There was almost an evangelical feeling about it. It seemed like it had almost died, and we wanted to make sure that never happened again.”

Free of the need to even contemplate what the commercial music industry might want of them, these new old-time musicians sought their own ways to create contemporary contexts in which the music could thrive.

This quest took two distinct, though parallel paths. The old-time revival that began in the late 1960s, and blossomed throughout the ‘70s, was like a twin-thrust engine, each power burst running on its own fuel, but serving the common goal of moving this music forward.

Savvy urban musicians like Trischka followed the cue of progressive bluegrass, reinventing the old music with modern jazz, pop, classical, rock and world beat influences.

Trischka describes this movement as a bi-coastal phenomenon. “There was the California thing with David Grisman, Darrol Anger, Mike Marhsall, and Tony Rice stretchng boundaries, combining bluegrass, western swing, jazz. But it was very organized in its way.”

“Then in New York, it was me, Kenny Kosek, Andy Statman, Stacy Phillips, and that whole crew, doing stuff that was even more out; taking klezmer and Hawaiian and jazz and rock and soul - anything we could get our hands on. Our music was a little rougher, more hell-bent-for-leather. A little more fur-bearing, you might say.”

At the same time, other musicians, like Ungar, sought ways to make this a real community music again. In 1971, with New Lost City Ramblers founder John Cohen, Ungar formed the Putnam String County Band in upstate New York. The goal was to be a concert band, but also to function as genuine village musicians, performing for local folk dances, seasonal celebrations, and other community gatherings. In fact, the playful name morphed from their original band, the Putnam County String Band, which had a slightly different cast. It played only for local dances, and refused to tour or record.

“I think many of us were quite aware that we were not from the culture that this music came from,” Ungar says. “We were trying to make our own family and community culture, and to have this music be its music. So naturally, the music changed somewhat in its form and function. We hoped we were creating a culture for this music, something we could live with for the rest of our lives, and pass on to our children.”

As traditional as their music might sound to us today, what Ungar’s band was doing was startlingly new, combining a keen knowledge of old-time traditions with a modern - and non-southern - eclecticism. The CD, for example, opens with the sweet drones of Abby Newton’s cello, heralding an entirely new ensemble approach to this music.

The music’s lack of commercial viability also inspired its devotees to develop alterntive ways to supplement their music incomes. They quickly realized they were, in fact, designing a modern equivalent to tradition itself, replicating ways for the music to pass from generation to generation. Players like Ungar and Trischka became interested in teaching, and in creating new environments for this music to be taught in the old, orally transmitted ways. Instruction cassettes and videos, music camps, and instructional workshops became important parts of their careers.

“The fiddle and banjo camps are like festivals, except you’re all learning,” Trischka says. “You get a bunch of people together who are all into the same thing, and really inculcate yourself.”

These immersion camps and workshops encourage a traditional style of learning, by ear from master players. As a result, much more than rudiments and techniques are passed along. Just as in the old days, the values and ethos of the music, the culture behind it, are passed from elders to students.

Ungar created a summer series of music and dance camps that became known as the Ashokan camps. As proof of how intense the immersion can be, his famous theme “Ashokan Farewell,” which was heard in Ken Burns’ epic documentary “The Civil War,” was written to express Ungar’s mood at the end of a particularly intimate camp week.

“The concept of marketing this music didn’t exist for us, even if we wanted to go that way, which we really didn’t,” Ungar says. “Nobody was into this music for that; it was more that you just wanted to make enough money so you could keep doing it.”

Adds his wife and current performing partner Molly Mason, “This music became your job in the community, something you do for everybody. There was no pretension that anybody was going to get rich at this, so on every level, it had a good feeling about it. It felt clean and honest.”

This movement toward teaching brought more young people into the music. It also encouraged even the most innovative artists to know more about the history of the music. Trischka may be a banjo revolutionary, but he also does shows tracing his instrument’s long history.

“As much as I’m into the progressive side, I’ve also gotten into the history,” he says, “and passing that along has become a passion for me over the years. You learn the roots of the music, and you just want to carry it on.”

In the ‘80s, a new generation, raised within this modern old-time culture, began to emerge. Unlike Ungar and Trischka, they had never known a world in which the music seemed perishable. They grew up believing it was their legacy, and they learned it in thriving musical communities, at fiddle camps, music contests, and pickin’ parties.

Alison Krauss is a prime example of this new generation. As a child, she competed in fiddle contests, and brings a lifelong immersion in traditional music into the modern musical arena.

Similarly, hot young bluesman Corey Harris is utterly at home in his provocative explorations of the African-American folk roots that begat the blues. While banked in ancient sounds, his artfully nuanced primitivism is as modern as hip-hop.

Another rising young star is 34 year-old multi-instrumentalist Dirk Powell. He first heard old-time music as a social form, played purely for fun by his grandfather. When he discovered young urban kids like himself gathering near his Ohio home for old-time jam sessions, he was hooked.

“This really seemed like a form in which you could express anything,” Powell says. “I also felt like it was totally noncommercial, in the sense that nobody was doing it with the first and foremost goal of selling records. As a teenager, you define yourself so much by the music you listen to, and at the time I was listening to punk, because it expressed a lot of things I was angry about, like how the place I lived seemed like such a big cultural vacuum. But I also knew that punk was an image that was being sold, and that was exactly what I was rebelling aginst.

“It started dawning on me that old-time music was just about the music, and a real exchange between people. That was the goal, just coming together to share something. It felt to me like this was really rebelling - not just railing against the system, but stepping completely outside of it and making music for its own sake.”

You won’t measure the real health of the old-time revival today by scanning the Billboard charts, but by the number of people picking up banjos and fiddles, and seeking out fellow pickers in neighborhood pubs, cellar coffeehouses, folk dances, and private homes. Elderly Instruments, a comprehensive folk instrument and supplies store with an international mail-order business, reports dramatic, steady increases in the sales of all folk instruments over the last few years, with a curve that’s trending only upward - even as pop record sales continue their historic decline.

Powell says, “I think of traditional music as a bottomless well; the more you take from it, the more you give to it. It’s a sustainable resource; that’s what’s so powerful about it, and why more people are listening to it and playing it today. So much of our social culture has succumbed to mass-marketing. I think a lot of American teenagers are floundering today because they’ve had all those necessary social ties pulled away from them. I was just lucky to have a grandfather who played the banjo.”

Scott Alarik, June, 2004

About the Artists, Part 1

Ola Belle Reed. Born in Asheville County, North Carolina in 1915, Reed was renowned for her earthy vocal style, clawhammer banjo, and devotion to the social heart of old time music. As a young woman, she declined an invitation to tour with Roy Acuff, feeling the the show-biz fast-lane might dampen her convivial, down-home love of the music. The hot vocal band Ollabelle is named in honor of Reed.

Bascom Lamar Lunsford. With his masterful five-string banjo playing and devotion to preserving the music, Lunsford transformed his home region of South Turkey Creek, North Carolina, into a celebrated old-time hotbed. He was a prolific collector of traditional music, and helped the world discover crucial regional artists like George Pegram and Red Parham.

Mike Seeger with Etta Baker. Seeger is the son of seminal ethnomusicologist Charles Seeger and composer Ruth Crawford Seeger, and stepbrother of folk icon Pete. As performer, folkloric collector, and archivist, he has done more to bring old time music to the world than perhaps anyone. Baker’s music was exquisitely poised where the black and white musical traditions of her native North Carolina intermingled.

George Pegram and Red Parham. Rounder Records was originally founded simply to preserve Pegram’s wonderfully raw, sweet banjo playing. Both he and singer-guitar-harmonica-player Parham were discovered by Bascom Lamar Lunsford.

Doc Watson and Gaither Carlton. No single performer did more to popularize old time music outside the south than blind North Carolina guitarist-singer Watson, who has remained a major star since the early days of the commercial folk revival. Carlton was Watson’s father-in-law.

Ginny Hawker. Born in Halifax County, Virginia, Hawker is a widely respected mountain singer first discovered by Hazel Dickens. She is married to New Lost City Ramblers alumnus Tracy Schwartz, with whom she frequently performs as a duo.

J.P. Fraley. A renowned master of the strong-bowed, vibrato-rich fiddle style of Eastern Kentucky, Jesse Presley Fraley often performed with his wife Annadeene. Together, they founded the popular Fraley Family Music Festival.

Buddy Thomas. Equally at home with brisk bluegrass dance tunes or melancholy mountain airs, Thomas was regarded as one of the last and finest exponents of the emotive fiddle style of northeastern Kentucky.

Sacred Harp singers of Georgia and Alabama. This gathering of nonprofessional shape-note singers from the Sacred Harp style popular in Georgia and Alabama was assembled especially for this 1977 recording by Hugh McGraw. “Traveller” was sung just as it would be in church.

Hazel Dickens. Born in Mercer County, West Virginia, Dickens is arguably the most important female old time singer and songwriter of the last 40 years. Her haunting vocal directness, populist urgency, and feminist fire made her popular both with both traditional and women’s music audiences, and her songs have been recorded by many modern artists, including Dolly Parton, Laurie Lewis, and Hot Rize.

Connie and Babe and the Backwoods Boys. Regional radio and recording stars around their Tennessee homes in the 1950s, their music is poised at the precise crossroads where old time music blossomed into bluegrass.

Dry Branch Fire Squad. With one foot firmly in the soil of old time music, the other tapping away to bluegrass, this band has remained in the front lines of the string band revival for nearly 30 years. Their stage shows are renowned for their musical vibrancy and smart country humor.

Hazel Dickens and Alice Gerard. Dickens first came to national prominence in a duo with Seattle native Gerard, who brought an urban polish to Dicken’s pure mountain style. They first performed in 1962 at a fiddler’s contest in Galax, Virginia.

Fuzzy Mountain String Band. The band grew out of the social music scene in Durham, North Carolina. Fondly dubbed “the Fuzzies,” the shaggy sextet formed in 1967, and is credited with helping translate the informal fun of an old-time pickin’ party to the concert stage.

Blue Sky Boys. Brothers Earl and Bill Bolick were contemporaries of the Monroe and Stanley brothers, but resisted their driving, bluegrass pulse. Their straightforward, spacious style, close, sweet harmonies, and subdued emotionalism are models of the classic mountain balladry from which both bluegrass and modern country music evolved.

Ralph Blizzard and the New Southern Ramblers. Blizzard championed a Tennessee fiddle style he called “Appalachian Mountain Longbow.” He was a regional star as a young man, then left music to support his family. He picked up the fiddle 25 years later to became revered as a traditional master and teacher.

Dirk Powell with Tim O’Brien. As solo artist and with his influential band Hot Rize, O’Brien has been in the vanguard of progressive bluegrass for over 20 years. Powell is a dynamic young multi-instrumentalist, equally at home with pure Appalachian tradition or recording with pop stars like Sting and Jewel. His banjo was heard in the the films “Cold Mountain” and “Bamboozled.”

About the Artists, Part 2

Putnam String County Band. Among the most important bands in fomenting the string-band and folk dance revivals, the upstate New York quartet was founded in 1971 by New Lost City Ramblers’ member John Cohen, Jay Ungar, his then-wife Lyndon Ungar, and pioneering folk cellist Abby Newton. Jay and Lyn’s daughter Ruth Ungar is the fiddler of the hot neo-trad band The Mammals.

Dirk Powell. Powell is a dynamic multi-instrumentalist, equally at home with pure Appalachian tradition or recording with pop stars like Sting and Jewel. His banjo playing was heard in the the films “Cold Mountain” and “Bamboozled.”

Mac Benford & the Woodshed All-Stars featuring Marie Burns. Benford was a founding member of the Highwoods String Band, arguably the most influential old-time string band of the ‘70s. Thanks in large part to Burns’ sultry vocals and songwriting, this band paved the way in fusing old-time to modern folk-pop.

Corey Harris. Colorado native Harris is a leader in the recent revival of blues among young African-Americans, and starred in Martin Scorcese’s acclaimed documentary “Feel Like Going Home.” He is also an important archivist and collector of neglected black traditional artists, such as the Rising Star Fife and Drum Band.

Tony Trischka with Northampton Harmony. Banjo star Bela Fleck calls Trischka “my springboard,” and compares his impact to that of Miles Davis or John Coltrane in jazz. Triscka is also an eminent banjo historian. Northampton Harmony was led by rising neotraditional star Tim Eriksen.

Jones and Leva. James Leva and Carol Elizabeth Jones were raised around string-band music. Though from New Jersey, Leva’s father performed for square dances, and Jones’ father headed the Appalachian Studies program at Kentucky’s Berea College.

Norman Blake. Blake’s spacious, elegantly melodic playing profoundly influenced the way southern folk music is played today. Raised in Georgia, he became a national star in Johnny Cash’s band in 1969, and subsequently on Bob Dylan’s “Nashville Skyline” album. Today, he performs chiefly with his cellist wife Nancy Blake.

James Bryan. The Alabama fiddler rose to prominence in Norman Blake’s Rising Fawn String Ensemble, but also performed with the Grand Ole Opry and Tennesse Ernie Ford.

Ron Block. Block plays banjo, guitar and sings with Alison Krauss + Union Station. His songs have been recorded by Krauss, Rhonda Vincent, Randy Travis, and the Cox Family.

Jay Ungar. Raised in the Bronx, Ungar became one of the architects of the northeastern string-band and folk-dance revivals, both as fiddler and with his popular music and dance camps in Ashokan, New York.

Rory Block and Lee Berg. In 1972, a gathering of acoustic stars in Woodstock, New York, made the hugely popular “Music from Mud Acres” records, combining the jamming vibe of an old-time pickin’ party with stellar musicianship. Block is among the most popular modern performers of folk blues.

Dry Branch Fire Squad. With one foot firmly in the soil of old time music, the other tapping away to bluegrass, this band has remained in the front lines of the string band revival for nearly 30 years. Their shows are renowned for their musical vibrancy and smart country humor.

Tony Furtado. Among the most innovative and respected of the “young turks” revolutionizing the way the banjo is played today, Furtado is also a great slide guitar player.

Riley Baugus. A North Carolina native, Baugus was reared on old-time music, learning to play from neighbors such as traditional masters Tommy Jarrell and Robert Sykes. He is also a banjo maker and blacksmith.

Fiddle Fever. Among the most innovative of the string-band revival bands, its members included Jay Ungar, Molly Mason, and Matt Glaser, chair of the string department at Berklee College of Music, and founder of the similarly inventive Wayfaring Strangers.

Lynn Morris. Among the most prominent female stars in bluegrass today, Morris was born in Texas, and twice won the National Banjo Championship. She has also won three Vocalist of the Year Awards from the International Bluegrass Music Association.

John Sebastian and Paul Butterfield. Two of the stars who took part in the Mud Acres sessions in Woodstock, NY. Sebastian founded the ‘60s folk-rock band the Lovin’ Spoonful. Butterfield’s eponymous ‘60s band fused Chicago blues to modern rock, and introduced the world to guitar legend Mike Bloomfield.

Alison Krauss + Union Station. Krauss is on her way to becoming the greatest crossover star in bluegrass history. She cut her teeth winnning fiddle contests as a child, and made her first record for Rounder in 1987, at 15. Among the finest and most influential singers anywhere in American music, she has already won more Grammies than any female artist in history (14).

Author’s Note. In 2004, Rounder Records released two CDs tracing the recorded history of old-time music, the term Southern rural people used to describe their traditional folk songs, tunes, and ballads. They asked me to write the liner notes, and what resulted was something of a primer for old-time music, and the culture from which it grew. I’ve combined both sets of liner notes here, to form a continuing narrative of old-time's evolution from the dawn of the commercial music industry to modern times, from Gid Tanner to Dirk Powell (both pictured above), Ola Belle Reed to Alison Krauss (both pictured below). At the end, there are brief biographies of every artist included in the two-volume anthology. One reason I enjoy writing liner notes is that I always learn so much, directly from the artists whose story is being told. Scott Alarik

In the remote southern mountains, however, where these social musical traditions thrived well into the 20th century, the folk had their own name for the music they made to accompany their daily lives. They called it old-time music.

It is, by form and function, starkly different from today’s commercial pop music. There is music for all the moments in people’s lives, from courting to dying, playing with children to working in the fields and mines. There are songs of adorable innocence and world-weary anguish, silly mischief and populist rage, seduction and heartbreak, ennobling hope and utter despair. What all the music shares is a visceral connection to the way real people live their lives.

Today, that realness is drawing people to old-time music more than at any time since the commercial folk revival of the 1960s. But this is no fleeting fad for Rounder Records. The Cambridge, MA., company was founded in large part to document the vanishing traditions of southern mountain music. It has since grown into the world’s most prolific and successful folk music label, but retains a special fondness for the raw splendor of southern mountain music.

“Mountain Journey” is the first of two CDs compiled from the Rounder archives as samplers of old-time music. This disc travels the backroads of the music’s roots. Though many crucial masters are here, it is not presented as an encyclopedia of stars or tunes, but more as a landscape, scanning the vistas of the music and how it actually lived among the people who created it.

Many people today are confused about the difference between old-time music and bluegrass. They are perfectly right to be confused, since bluegrass has, at its core, the repertoire of old-time music. Bluegrass is, in fact, a relatively recent offshoot of old-time music, growing from its ancient soil little more than 60 years ago.

Performer-archivist-collector Mike Seeger has done as much as anyone to popularize, preserve, and document old-time music. He believes the line between old-time and bluegrass is best observed by listening to what makes bluegrass unique: its tight, ensemble sound and driving cadence, fueled by the Earl Scruggs three-fingered banjo style, downbeat bass beat, and the off-beat mandolin rhythm chops pioneered by Bill Monroe.

Though many of the tunes on this CD are also quick and propulsive, little of that unique bluegrass groove, or its trademark high, lonesome harmonies, is heard. But listen closely, and you will hear the roots of all those things.

Seeger’s mother, the influential musicologist and composer Ruth Crawford Seeger, properly described old-time as “a folk name for folk music.” It describes all the traditional music embraced by southern mountain folk.

“Bluegrass is one kind of music,” Mike Seeger says, “and old-time is many kinds of music. Bluegrass is a music that grew out of both black and white southern traditional music. And it evolved primarily as a performance music, while old-time music, at its heart, is a social music, a folk form in the oldest and purest sense of the term.”

Hazel Dickens is one of the most influential living singers of old-time music. Born in Mercer County, West Virginia, she grew up around the last echoes of the purely social old-time traditions, before records and radios offered new, impersonal ways to hear music. While she was as likely to learn a song off the radio as from her singing parents, she saw music still made to accompany the lives of her community.

She particularly noticed how completely the old music punctuated the lives of her parents. Her father walked 15 miles across the mountains to court her mother, after which they would sing and play music all night long.

“The music permeated everything they did socially in those days,” Dickens says, “because there was nothing else to do but go to church and play music. Of course, music was a big part of church, too.”

Most of the quickstep fiddle and banjo tunes were, at heart, dance tunes, many with melodic roots in Ireland, Scotland, and England. They would be played as people danced, either at community dances or house parties. Frisky ditties called “frolic songs,” such as “Cripple Creek,” were often danced to as well.

The call to the dance is vibrantly heard on J.P. Fraley’s classic rendition of “Wild Rose of the Mountain.” By contrast, Buddy Thomas’ “Sweet Sunny South” is done more in the expressive style of the air, or instrumental tune meant for listening.

Ballads, or story-songs, laments, and love songs would be shared in evenings, around the fire or potbellied stove. They were the night’s entertainment, often igniting spirited discussions about their meaning and lessons.

That’s also when a wistful song like “Pretty Bird,” which Dickens wrote in the old style, would most likely be sung. The powerful dissonance of close mountain harmonies is wonderfully heard in her duet with Ginny Hawker on the aching populist lament, “Times Are Not What they Used to Be.”

Seeger says these songs were used at other times as well: “Ballads, love songs, and frolic songs would also be sung during breaks from the workday, at the end of a row in the fields. Or when it was ‘layin’-by’ time, the slow times like winter. Also at night when the kids were going to sleep, or in the morning when mom was cooking over the woodstove.”

The vocal traditions originated as a chiefly unaccompanied style, later adapted to fit the accompaniment of banjo and guitar. In the opening track, legendary North Carolina singer Ola Belle Reed offers a gorgeous essay in the evolution of the old-time vocal style. While her guitar tinkles sparely, she begins in the old, unaccompanied style, her cadence shaped by the emotion of the lyric. Then her guitar takes the lead, the tempo tightens, and her phrasing compresses to suit the guitar. Not better, not worse; just different.

Though old-time describes primarily the folk music of the white rural south, its intermingling with African-American tradition was a rich stream that flowed between both cultures. Slaves developed the banjo from stringed instruments in their native Africa, but it was played as a white folk instrument by the early 1700s. Similarly, blacks picked up white instrumentals (called tunes) and vocal songs, adding their own distinctive stamp, which, in turn, found its way back into the way whites performed the music.

African-American old-time and blues musician Etta Baker proves how vibrantly white traditions existed in her community in her coy, sprightly duet with Seeger on “Cripple Creek.” Similarly, the black nuance we have come to call the blues influence, though it actually predates the blues, is hauntingly evident in old-time giant Doc Watson’s singing of “And Am I Born to Die?”

Church dominated the lives of most mountain people. There were liturgical hymns sung mainly in church, but also a vast repertoire of sacred songs that were heard at all times. Much of the liturgical repertoire was spread in hymnals called “shape-note books,” because of a clever iconic system developed in the 1800s to allow illiterate people to read musical notation. The simple, sturdy harmonies allowed for much freedom of emotional expression.

One branch of that tradition is called Sacred Harp, after one of the most popular of these 19th-century hymnals. It can still heard at rural churches in Georgia and Alabama, as captured in “The Traveller.”

New music technologies, beginning with the first radios and phonographs, gradually displaced the old traditions. But even as they faded, they were being documented, recorded, and taken up by modern folk artists like Seeger. During the ‘60s folk revival, Seeger’s band the New Lost City Ramblers popularized old-time music throughout the country, creating legions of new fans at college campuses and coffeehouses.

Savvy professional performers with old-time roots, such as Doc Watson and Hazel Dickens, became national stars. Just as importantly, communities of nonprofessional musicians and folk dancers sprang up all over the country, who eagerly embraced old-time music as the social form it was at heart. Old-time pickin’ parties, festivals, fiddle and banjo camps, and folk dances became cultishly popular, and actually grew as the commercial folk revival declined.

Dickens watched the transformation of the music brought on by the commercial folk revival, and even earlier by the ensemble rigors of bluegrass.

“As the music got heard on the radio more, and performed by professional musicians,” she recalls, “it got more polished, slicker. I don’t mean the songs themselves changed, but people became more aware that it was not parlor music anymore, the way we’d always known it. We’d hear people like Jim and Jesse on the radio, and their playing was so impeccable. When it gets that good, everybody feels a little challenged by it; that if they want to play it, boy, they’ve got to really step up to the plate. It wasn’t like the old raw stuff you felt you could just pull up a chair and join in with. It took some of the fun out of it.”

Thankfully, most popular old-time stars, like Seeger and Dickens, worked to ensure that the music also retained its carefree, nonprofessional identity, and became powerful allies in the social revivals of the music, which are chronicled in Volume 2 of Rounder’s old-time odyssey, “Come to the Mountain.”

“Almost every place I’ve gone to sing,” Dickens says, “there’s a social scene, pockets of people just getting together to play the music for fun, the way it’s meant to be. I don’t think people realize how many nonprofessionals there are who still play this music. There’s no way to calculate the joy it brings to people like that, people who would never think of playing the music for money, and yet they get immense pleasure from learning the songs, getting their spouse to sing a harmony. It’s stayed truer to itself that way than some other musics have, I think.”

Scott Alarik, June, 2004

Old Time Music, part 2. “Come To the Mountain”

Old-time music is the term southern folk use to describe their folk music. Long after similar traditions had faded in most parts of the country, this vibrant, self-made music - dance tunes and frolic songs, tragic ballads and wistful love songs - coninued to pass from generation to generation in remote, rural areas of the south, particularly in the mountains. Though it formed the root of both country music and bluegrass, old-time music in all its wild, folksy grace was rarely heard outside the communities that created it.

The commercial folk revival of the 1960s changed all that, exposing the music to millions of people all over the world. This CD, the companion to Rounder’s more purely traditional old-time homage “Mountain Journey,” chronicles how this uniquely southern music traveled and was transformed by the ‘60s revival; and by the string-band and folk-dance revivals that followed in its wake, and are still thriving today.

In Syracuse, New York, a kid weaned on classical music, jazz, and Broadway show tunes heard an old-timey banjo break in the 1963 Kingston Trio hit “Charlie on the MTA.” “It literally forced me to play the banjo,” Tony Trischka recalls. “I calll them the 16 notes that ruined my life.”

Around the same time, a violin prodigy in the Bronx was enrolled in the prestigious High School of Music and Art. Classmates played him obscure recordings of vintage old-time musicians. Classical music lost a promising violinist, but old-time music got itself one helluva fiddler in Jay Ungar.

This new generation of fans watched as the increasingly commercial folk revival turned away from traditional forms like old-time music. Rounder Records, from whose archives all the selections here come, was founded in 1970, its original mission to record old-time musicians the folk revival was ignoring.

In a sweet irony, the music’s lack of commercial viability became its greatest asset.

“There was the lingering notion that this music could die away,” Ungar recalls. “That was a very strong feeling among nearly all of the people who came into the music in the late ‘60s and ‘70s. There was almost an evangelical feeling about it. It seemed like it had almost died, and we wanted to make sure that never happened again.”

Free of the need to even contemplate what the commercial music industry might want of them, these new old-time musicians sought their own ways to create contemporary contexts in which the music could thrive.

This quest took two distinct, though parallel paths. The old-time revival that began in the late 1960s, and blossomed throughout the ‘70s, was like a twin-thrust engine, each power burst running on its own fuel, but serving the common goal of moving this music forward.

Savvy urban musicians like Trischka followed the cue of progressive bluegrass, reinventing the old music with modern jazz, pop, classical, rock and world beat influences.

Trischka describes this movement as a bi-coastal phenomenon. “There was the California thing with David Grisman, Darrol Anger, Mike Marhsall, and Tony Rice stretchng boundaries, combining bluegrass, western swing, jazz. But it was very organized in its way.”

“Then in New York, it was me, Kenny Kosek, Andy Statman, Stacy Phillips, and that whole crew, doing stuff that was even more out; taking klezmer and Hawaiian and jazz and rock and soul - anything we could get our hands on. Our music was a little rougher, more hell-bent-for-leather. A little more fur-bearing, you might say.”

At the same time, other musicians, like Ungar, sought ways to make this a real community music again. In 1971, with New Lost City Ramblers founder John Cohen, Ungar formed the Putnam String County Band in upstate New York. The goal was to be a concert band, but also to function as genuine village musicians, performing for local folk dances, seasonal celebrations, and other community gatherings. In fact, the playful name morphed from their original band, the Putnam County String Band, which had a slightly different cast. It played only for local dances, and refused to tour or record.

“I think many of us were quite aware that we were not from the culture that this music came from,” Ungar says. “We were trying to make our own family and community culture, and to have this music be its music. So naturally, the music changed somewhat in its form and function. We hoped we were creating a culture for this music, something we could live with for the rest of our lives, and pass on to our children.”

As traditional as their music might sound to us today, what Ungar’s band was doing was startlingly new, combining a keen knowledge of old-time traditions with a modern - and non-southern - eclecticism. The CD, for example, opens with the sweet drones of Abby Newton’s cello, heralding an entirely new ensemble approach to this music.