Articles

Robert Burns & Woody Guthrie: Two Of a Kind?

Saturday, October 7, 2006

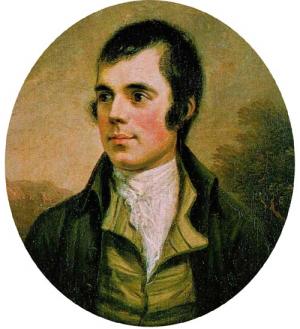

Almost anywhere you go in the English-speaking world, when people talk about ''the Bard," they mean William Shakespeare. In Scotland, it's Robert Burns. For more than 200 years, the late 18th-century Scottish poet and songwriter has been the defining national icon of his native land, his image emblazoned on cookie tins and souvenir banners, much the way the harp is displayed in Ireland. He wrote many of the most familiar poems of his age, including ''Tam O'Shanter," and ''To a Mouse," with its oft-quoted line ''The best-laid schemes o' mice an' men/Gang aft a-gley" (that is, ''often go awry"). He also wrote or popularized hundreds of songs, including ''Auld Lang Syne" and ''Comin' Thro' the Rye," which inspired the title of J.D. Salinger's novel ''The Catcher in the Rye."

Burns's songs have long been the province of prim sopranos and Tartan-kilted tenors, his poems wheezily recited at formal banquets called Burns Suppers. But strange things are happening to the old boy's image today. A very different Burns--a decidedly hipper model--is emerging in Scotland, embraced by a new generation of Scottish musicians and cultural activists. One might say he is being transformed from Scotland's Shakespeare into its Woody Guthrie.

''Burns has never been more popular than he is now, and in a very contemporary way," says Fiona Ritchie, the Scottish host of the National Public Radio program ''Thistle and Shamrock." ''More and more, musicians feel comfortable arranging his songs in ways that speak to people's tastes today."

Yet Burns is not being reinvented so much as revalued. After centuries as Scotland's supreme poet, he is increasingly being heralded as its supreme musician. ''For about 200 years," says University of Edinburgh professor Fred Freeman, who produced the ''Complete Songs of Robert Burns" CDs for the Scottish label Linn Records. ''I think Burns has been grossly misrepresented. He was primarily a songwriter, wrote many more songs than poems. He was also a serious fiddler."

More than ever, Burns's songs are being performed by popular Celtic acts, such as the hot Scottish band Old Blind Dogs and Dougie MacLean. Scottish alt-pop diva Eddi Reader, who cut her teeth with the Eurythmics and Gang of Four, recently released a beautifully urbane CD of Burns's songs on Compass Records. Four years ago, a major festival called Burns An A'That was founded near his home in Ayr. Last month's lineup included such unlikely Burns champions as Lou Reed and the Traschcan Sinatras. And in 2002, Linn Records completed its sublimely folksy 12-CD series--marking the first time in history that all 368 of Burns's songs have been recorded.

''It always takes people to just hear something in a different way," Reader says. ''And that's been happening with Burns lately. He is now being seen as a vital artist, rather than some stuffy old thing in a school cupboard."

The similarities between Burns and Woody Guthrie are striking. Like Guthrie, Burns was a genius of humble origins, dubbed ''the Ploughman Poet," just as Guthrie became ''the Dust Bowl Troubadour." Also like Guthrie, Burns was an outspoken populist. He railed against rogues in high places, championed the poor and oppressed, and wrote stunningly precocious warnings about the dangers of abusing the environment. He also wrote with simmering sexuality, penning seductively romantic love songs, winking flirtations, and bawdy ballads.

And yet, at the very moment Burns became famous, Scottish culture was seeking to identify itself more closely with polite British society. Beginning early in his career, he was lionized more as the young poet who was the toast of the British elite, and welcomed into the posh drawings rooms of Edinburgh, even offered a chance to stand for Parliament. But he turned his back on all that; partly for the love of his life, Jean Armour; partly because he preferred the simple life of rural Scotland; and partly because he had no inheritance to live on while wallowing among the gentry.

Until quite recently, scholars and biographers often faulted his decision to reject high society in order to spend his life among the humble folk. Today, however, that return to the countryside is seen as his defining moment, igniting his most important work. He turned his genius from drawing-room verse to songwriting, and to collecting hundreds of traditional songs, which were preserved in songbooks carrying his famous name. His most popular song, ''Auld Lang Syne," is actually one of those he collected. Though many believe he rewrote it, he insisted he simply ''took it down from an old man's singing."

Burns described himself as ''a fiddler and a poet," and he meant it in that order. To help preserve the traditional music he loved, he set most of his songs to Scottish fiddle tunes with complex dance rhythms: jigs, reels, strathspeys, and hornpipes. He told friends the melodies then had two chances to survive, as fiddle tunes and as the published works of a popular poet.

The unique way he wrote songs has kept musicians from being able to perform most of them authentically until quite recently. Until a few years ago, Scotland had few professional musicians with the right muscles to master those kinds of songs. As in most European traditions, the Scottish song and instrumental repertoires are distinct. Folk ballad singers, and even classically trained vocalists, were rarely acclimated to the quickstep disciplines of the jig. So only his best known and most ballad-like songs tended to be heard.

The current Celtic music revival's emphasis on ensemble instrumental playing has created what Freeman calls ''the correct instrument" to perform Burns's songs. Singers like Jim Malcolm of Old Blind Dogs are comfortable singing a ballad one moment, then pounding out guitar rhythms to a breathless reel.

Malcolm respects Burns, the poet, and is currently setting his poem ''Tam O'Shanter" to music. But he adores Burns the fiddler.

''His songs are being valued today more than his poems," Malcolm says. ''And when you add to the mix what a great musician he was, it becomes even more clear what a genius he was. There's an expression that all modern philosophy is footnotes to Plato. You could almost say that Scottish culture is all footnotes to Burns."

Eddi Reader says, ''I found my way into Burns's music by seeing him as a Tom Waits or a David Bowie. When I came at it from that angle, I felt like I was being a bit haunted by him--that he would've been encouraged that I wasn't doing it as a classical or historical exercise, but because I was having a living relationship with him."

Originally appeared in The Boston Globe

Burns's songs have long been the province of prim sopranos and Tartan-kilted tenors, his poems wheezily recited at formal banquets called Burns Suppers. But strange things are happening to the old boy's image today. A very different Burns--a decidedly hipper model--is emerging in Scotland, embraced by a new generation of Scottish musicians and cultural activists. One might say he is being transformed from Scotland's Shakespeare into its Woody Guthrie.

''Burns has never been more popular than he is now, and in a very contemporary way," says Fiona Ritchie, the Scottish host of the National Public Radio program ''Thistle and Shamrock." ''More and more, musicians feel comfortable arranging his songs in ways that speak to people's tastes today."

Yet Burns is not being reinvented so much as revalued. After centuries as Scotland's supreme poet, he is increasingly being heralded as its supreme musician. ''For about 200 years," says University of Edinburgh professor Fred Freeman, who produced the ''Complete Songs of Robert Burns" CDs for the Scottish label Linn Records. ''I think Burns has been grossly misrepresented. He was primarily a songwriter, wrote many more songs than poems. He was also a serious fiddler."

More than ever, Burns's songs are being performed by popular Celtic acts, such as the hot Scottish band Old Blind Dogs and Dougie MacLean. Scottish alt-pop diva Eddi Reader, who cut her teeth with the Eurythmics and Gang of Four, recently released a beautifully urbane CD of Burns's songs on Compass Records. Four years ago, a major festival called Burns An A'That was founded near his home in Ayr. Last month's lineup included such unlikely Burns champions as Lou Reed and the Traschcan Sinatras. And in 2002, Linn Records completed its sublimely folksy 12-CD series--marking the first time in history that all 368 of Burns's songs have been recorded.

''It always takes people to just hear something in a different way," Reader says. ''And that's been happening with Burns lately. He is now being seen as a vital artist, rather than some stuffy old thing in a school cupboard."

The similarities between Burns and Woody Guthrie are striking. Like Guthrie, Burns was a genius of humble origins, dubbed ''the Ploughman Poet," just as Guthrie became ''the Dust Bowl Troubadour." Also like Guthrie, Burns was an outspoken populist. He railed against rogues in high places, championed the poor and oppressed, and wrote stunningly precocious warnings about the dangers of abusing the environment. He also wrote with simmering sexuality, penning seductively romantic love songs, winking flirtations, and bawdy ballads.

And yet, at the very moment Burns became famous, Scottish culture was seeking to identify itself more closely with polite British society. Beginning early in his career, he was lionized more as the young poet who was the toast of the British elite, and welcomed into the posh drawings rooms of Edinburgh, even offered a chance to stand for Parliament. But he turned his back on all that; partly for the love of his life, Jean Armour; partly because he preferred the simple life of rural Scotland; and partly because he had no inheritance to live on while wallowing among the gentry.

Until quite recently, scholars and biographers often faulted his decision to reject high society in order to spend his life among the humble folk. Today, however, that return to the countryside is seen as his defining moment, igniting his most important work. He turned his genius from drawing-room verse to songwriting, and to collecting hundreds of traditional songs, which were preserved in songbooks carrying his famous name. His most popular song, ''Auld Lang Syne," is actually one of those he collected. Though many believe he rewrote it, he insisted he simply ''took it down from an old man's singing."

Burns described himself as ''a fiddler and a poet," and he meant it in that order. To help preserve the traditional music he loved, he set most of his songs to Scottish fiddle tunes with complex dance rhythms: jigs, reels, strathspeys, and hornpipes. He told friends the melodies then had two chances to survive, as fiddle tunes and as the published works of a popular poet.

The unique way he wrote songs has kept musicians from being able to perform most of them authentically until quite recently. Until a few years ago, Scotland had few professional musicians with the right muscles to master those kinds of songs. As in most European traditions, the Scottish song and instrumental repertoires are distinct. Folk ballad singers, and even classically trained vocalists, were rarely acclimated to the quickstep disciplines of the jig. So only his best known and most ballad-like songs tended to be heard.

The current Celtic music revival's emphasis on ensemble instrumental playing has created what Freeman calls ''the correct instrument" to perform Burns's songs. Singers like Jim Malcolm of Old Blind Dogs are comfortable singing a ballad one moment, then pounding out guitar rhythms to a breathless reel.

Malcolm respects Burns, the poet, and is currently setting his poem ''Tam O'Shanter" to music. But he adores Burns the fiddler.

''His songs are being valued today more than his poems," Malcolm says. ''And when you add to the mix what a great musician he was, it becomes even more clear what a genius he was. There's an expression that all modern philosophy is footnotes to Plato. You could almost say that Scottish culture is all footnotes to Burns."

Eddi Reader says, ''I found my way into Burns's music by seeing him as a Tom Waits or a David Bowie. When I came at it from that angle, I felt like I was being a bit haunted by him--that he would've been encouraged that I wasn't doing it as a classical or historical exercise, but because I was having a living relationship with him."

Originally appeared in The Boston Globe